Cabo Ligado Monthly: January 2024

January At A Glance

Vital Stats

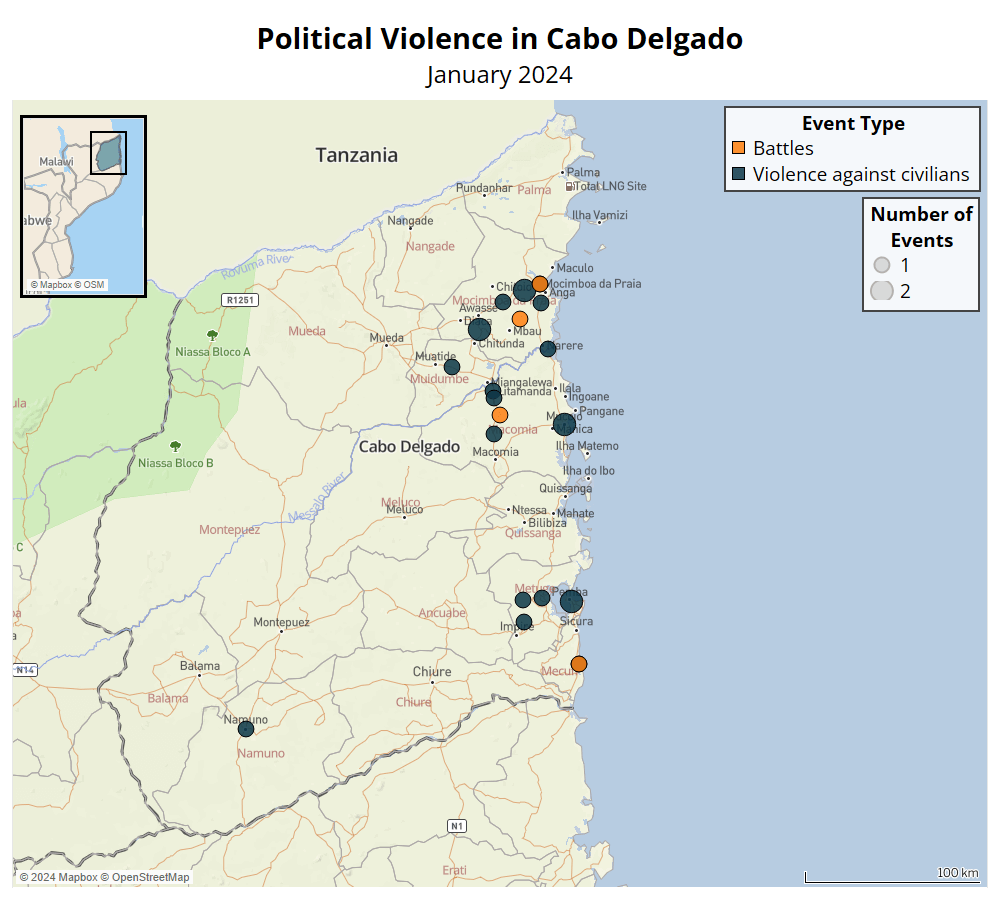

ACLED records 28 political violence events in Cabo Delgado in January, resulting in at least 25 reported fatalities

Twenty-one of the reported events were incidents targeting civilians

Events were concentrated in Mocímboa da Praia, Macomia, Metuge, Pemba and Mecufi districts

Vital Trends

ISM was involved in 22 political violence events in January, three times as many as in the previous month

ACLED records at least 21 fatalities in incidents targeting civilians, the highest since December 2022

The Naparama militia was involved in four incidents related to the cholera outbreak

In This Report

The insurgency threatens the south

Implications of electoral law changes for Cabo Delgado

Tanzania’s view of regional security

January Situation Summary

January saw the struggle for control of the Macomia coast and its islands continue, as well as a significant push southwards by Islamic State Mozambique (ISM). More actions by the Naparama militia in southern Cabo Delgado were a reminder that communities’ lack of trust in the state can present itself violently outside of the frame of the insurgency.

On 21 January, ISM took control of Mucojo village in Macomia district after the Defense Armed Forces of Mozambique (FADM) abandoned an outpost there. FADM’s flight came in the wake of threats by ISM arising from at least two incidents in which FADM targeted and killed civilians in Mucojo and neighboring villages in the previous week.

ISM was involved in three times as many violent events in January as in December, with the vast majority of these incidents being attacks on civilians. ACLED records at least 21 fatalities in such incidents. While the month was notable for the group’s push southwards, more than half of those killings were in Mocímboa da Praia district, north of ISM’s stronghold in Macomia.

In Ancuabe, Montepuez, and Namuno districts, the Naparama militia targeted facilities associated with the government’s response to the ongoing cholera epidemic. Given similar incidents in December, and the violence that followed the municipal election in Chiure, such violence is indicative of fault lines in Cabo Delgado that remain widespread and deep-rooted.

The Insurgency Threatens the South

By Tom Gould, Cabo Ligado

January saw the center of gravity in the conflict in Cabo Delgado shift south, as insurgents vied with security forces for control of the strategic coastal village of Mucojo in Macomia district while dispatching fighters to Quissanga, Metuge, Mecúfi, and Chiure districts.

For most of 2023, Mucojo represented the southern limit of insurgent activity, with attacks largely concentrated along the Macomia coast, around the N380 highway, or in Muidumbe and Mocímboa da Praia districts. ISM reorganized its movements after FADM abandoned Mucojo on 18 January, allowing insurgents to occupy the village and secure access to the sea.

Mucojo was the first substantial settlement to be occupied by insurgents since they were expelled from the towns of Mocímboa da Praia and Mbau in August 2021 by Rwandan Security Forces (RSF) Unlike in these examples, where civilians were displaced from the area, insurgents in Mucojo immediately set about installing the trappings of a caliphate over the remaining population. A strict interpretation of Sharia, or Islamic law, was imposed, including the banning of certain haircuts, the sale of alcohol, and tight or tapered trousers. Meanwhile, daily prayers and attendance at mosques were encouraged.

The Islamic State (IS) newspaper al-Naba reported on 25 January that its fighters were using their newfound freedom of movement along the Macomia coast to travel from village to village by boat, preaching to civilians and warning them “of the danger of aiding the infidels.” This marked one of the first times since the beginning of the conflict in 2017 that the insurgents have made a serious attempt to spread and enforce Islamic teachings.

Mucojo also became a staging post for a daring thrust into districts to the south where insurgents have rarely set foot. On 19 January, insurgents began arriving in Quissanga district and appeared four days later in Mussomero village, just four kilometers from the district capital. Insurgents moved onto Metuge district on 25 January, bordering the provincial capital Pemba, and appeared to split into two groups, with some continuing directly south to Mecúfi, while others marched southwest toward Ancuabe district.

On 30 January, an insurgent ambush near Nahavara, in Mecúfi, left eight FADM troops and members of the Local Force dead. Insurgents also burned houses and kidnapped several people in the nearby village of Makwaya on the same day. Around 1,460 people fled their homes between 22 January and 2 February due to these incidents, according to the International Organization of Migration. Mecufi had not suffered an insurgent attack since June 2022.

Security forces retook Mucojo without a fight by 31 January, but the fact that they abandoned it in the first place exposes alarming weaknesses in Cabo Delgado’s security apparatus. As the withdrawal of the Southern African Development Community Mission in Mozambique in July looms, Mozambican forces are still struggling to demonstrate their capability to contain the insurgency.

This weakness has emboldened the insurgency to undertake more aggressive operations and even present itself as an alternative to the Mozambican state. ISM’s attempts to impose Sharia, even if they are short-lived, will undo the narrative pushed by the security forces that the insurgency in Cabo Delgado is under control.

Implications of Electoral Law Changes for Cabo Delgado

By Tomás Queface, Cabo Ligado

In 2024, Mozambique will go to the polls for presidential, legislative, and provincial elections. For this, the register of voters needs to be updated. According to Mozambican law, voter registration should take place six months after the election is announced. As the Council of State announced 9 October 2024 as the election date back on 7 August 2023, voter registration should have started by law in February. However, the fact that this falls in the rainy season means the voter registration needed to be rescheduled. This will require further changes to electoral laws and have implications for the electoral process in general. The insurgency in Cabo Delgado could also affect the registration process and the holding of the upcoming elections.

January and February this year coincided with the peak of the rainy season, especially in northern Mozambique. This impact was real in Cabo Delgado. In January, rains caused the EN380 bridge to collapse, cutting off the overland link between Macomia and the municipalities of Mocímboa da Praia, Mueda, Nangade, and Palma. In the district of Mecufi, in the south of Cabo Delgado, more than 9,000 people were trapped, agricultural fields were flooded and there was a lack of access to food aid for the victims of the floods as a result of the Megaruma River overflowing its banks.

In light of these realities, Frelimo on 11 January proposed an amendment to the law on voter registration, Law No. 8/2014 of 12 March, to allow the dates to be pushed forward. Subsequently, parties in parliament voted by consensus on 24 January to amend the law to change the start of voter registration to nine months after the announcement of the election date rather than six months. Voter registration will therefore take place between 15 March and 28 April, according to the Council of Ministers.

In practice, this change will require an overhaul of the electoral calendar and the need to amend other laws to reflect such changes. The changes proposed by Frelimo aim to address logistical challenges due to the rainy season, but raise concerns about fairness and equal opportunities for smaller parties in the upcoming elections. This change to the electoral calendar will reduce the time opposition parties have to prepare their candidacy papers. For the provincial elections, the deadline for parties and candidates to submit their papers will be reduced from two months to three weeks. And the deadline for provincial assembly candidates will be reduced from two months to 20 days. This is a big problem for people in rural areas, who sometimes have to travel to the major towns to get this document.

Insurgent attacks could also affect voter registration in Cabo Delgado. With voter registration set to begin on 15 March, the National Electoral Commission is expected to conduct registration only in district and municipal headquarters where there is adequate security, according to the Centre for Public Integrity. During last October's municipal elections, the only municipality where there were concerns about the holding of elections was Mocimboa da Praia. However, the presence of Mozambican and Rwandan troops meant that the process went ahead without any insurgent attacks. The situation is different for the general elections, which will take place in all the villages, towns, and districts of Cabo Delgado. With insurgent attacks occurring in Macomia, Mecufi, Metuge, Mocímboa da Praia, Muidumbe, and Pemba districts in January alone, the electoral process is under immediate threat. Even the distribution of voter registration material to the main villages and town centers could be affected by attacks on villages and towns along the EN380, particularly on the Macomia-Oasse route.

According to the Mozambican Constitution, universal suffrage is the general rule for the election of members of elective bodies at all levels. The disruption of voter registration will prevent many people in Cabo Delgado from voting and being elected as representatives and members of provincial assemblies, deputies, and other elective bodies. Without this universal right, they will not be able to express their grievances or participate directly in debates and decisions on issues that affect them through elections. There is no solution in sight to ensure that this constitutional right is respected, given the insecurity in some parts of Cabo Delgado. National and foreign forces are restricted in their ability to deploy throughout the province of Cabo Delgado. If there is no other legal way out, parliament could be asked to change the electoral law again.

Tanzania’s View of Regional Security

By Peter Bofin, Cabo Ligado

Two speeches in Dar es Salaam on 22 January gave a rare insight into Tanzania’s view of regional security issues. General Jacob John Mkunda, Chief of Defence Forces (CDF), and President Samia Suluhu Hassan were speaking at the Seventh Meeting of the CDF and Commanders. They highlighted how Tanzania’s internal security is linked to conflicts in the region, including in Cabo Delgado, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Both touched on recruitment for armed groups in the region within Tanzania, the deployment of the Tanzania People’s Defence Force (TPDF) in Mozambique, and the security risks presented by refugees. Touching all these issues, one way or another, is Rwanda.

General Mkunda first highlighted the “growing problem” of “terrorism and extremism,” speaking of youth aged 15-35 being radicalized and sent to join “terrorist groups, in particular in DRC, Mozambique, and Somalia.” President Samia returned to the subject later. “We can’t say they are Mozambican groups or DRC groups,” she said. “They are groups of Tanzanians as long as there are Tanzanians in them.” For President Samia, maintaining internal security would depend on conflicts in such countries not spilling over into Tanzania, either through the return of Tanzanians involved in such groups or through communities of refugees from neighboring countries becoming channels for the entry of small arms into the country.

General Mkunda presented little new about Tanzania’s security operations in southern Tanzania and northern Mozambique and was correct to state that security operations have prevented the conflict from spilling over into Tanzania. President Samia, in her remarks, echoed this but mentioned the presence of two separate forces on the border that prompted Tanzania to establish a bilateral security arrangement with Mozambique. One was the “terrorist” group which “crosses from time to time to commit acts of terror on our side.” In a clear reference to the RSF deployed in Palma, her other concern is a “foreign force which is beside our border.”

President Samia did not expand on Tanzania’s concerns about Rwanda. Indeed, Rwanda was not mentioned when the conflict in Cabo Delgado was discussed. This reticence was likely due to Tanzania’s involvement in the Southern African Development Community Mission in DRC (SAMIDRC), which is now fighting the M23 Movement in North Kivu province, alongside the bilaterally deployed National Defence Force of Burundi. M23 is widely considered to be backed by Rwanda, while RSF was reportedly active there as recently as 7 February.

One element of conflict spillover from Mozambique that Tanzania has prevented is refugee flows. Refugees that have arrived, most notably after the attack on Palma in March 2021, have been quickly returned. Tanzania has been adamant that long-term refugee settlements in the northwest have been a significant source of insecurity. It has prevented the growth of such settlements in southern Tanzania, and in recent years has been pushing for the return of refugees in the northwest to Burundi and DRC. At the Dar es Salaam meeting, General Mkunda stressed this point, accusing them of being “unsuccessful asylum seekers and economic migrants.”

There is evidence that refugee settlements in Tanzania’s Kigoma region are sites of political violence. Over the past five years, ACLED data show Kigoma region to have the highest rates of political violence in Tanzania over the past five years, concentrated in Mtendeli, Nduta, and Nyarugusu refugee camps there. However, the recent spikes in violence followed a 2019 repatriation agreement between Tanzania and Burundi. Violence against civilians by police accounted for a significant number of such incidents recorded.

Tanzania’s refugee burden, for the most part, arises from unrest in the Great Lakes countries. What direction that will take while the Tanzania contingent of SAMIDRC is in conflict with M23 in DRC, and President Samia is suspicious of Rwanda’s presence across the border in Mozambique, remains to be seen.