Cabo Ligado Monthly: November 2020

November at a Glance

Vital Stats

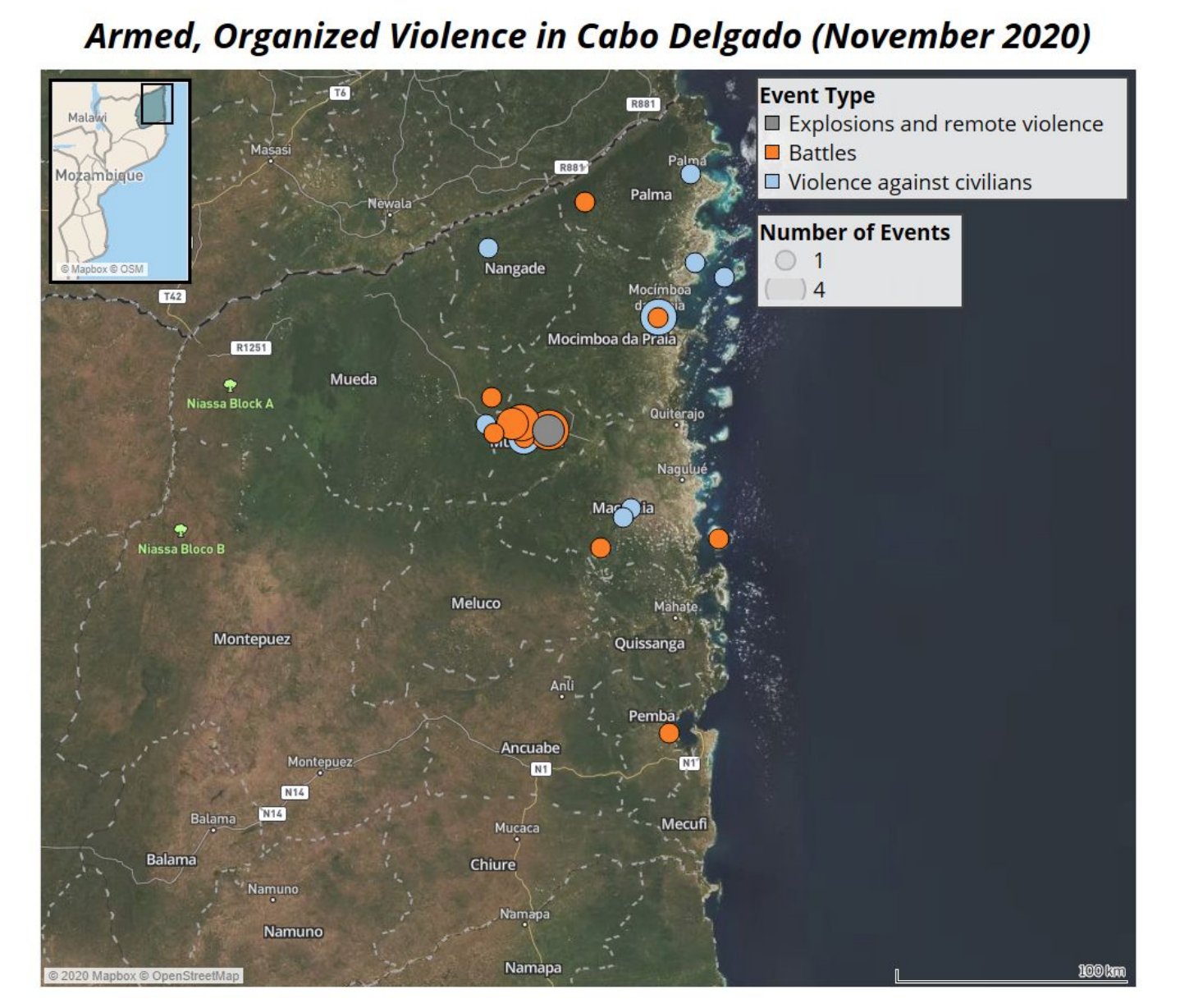

ACLED recorded 37 organized political violence events in November, resulting in 171 fatalities

The violence was deadliest in Muidumbe district, where 122 people died, most of whom were civilians killed by insurgents during their occupation of towns along the road through Muidumbe to Mueda

Other events took place in Ibo, Macomia, Metuge, Nangade, and Palma districts

Vital Trends

Insurgents dramatically increased their use of deadly violence as a tool to terrorize civilians during their ongoing occupation of large swaths of Muidumbe district

The implicit threat to Mueda posed by insurgent forces massed in Muidumbe further constrained government action, as other insurgent forces were able to threaten areas of Nangade and western Palma district free from the reprisal of Mueda-based government forces

Local militias based in Mueda joined police in offensive operations against insurgents in Muidumbe district, a first for militias in the conflict

In This Report

Analysis of the potential use of child soldiers in the Cabo Delgado conflict

An update on the role of local militias in the conflict

The latest on Mozambique’s efforts to solicit outside assistance for its counterinsurgency effort

November Situation Summary

Insurgents in Cabo Delgado undertook a sustained and deadly offensive in Muidumbe district in November, targeting civilians at a scale unprecedented in the conflict thus far. In addition to causing death and destruction within Muidumbe, the offensive has put the government on the back foot militarily. It has forced even more displacement of civilians, including among the already displaced refugees in Mueda. At the end of the month, the north of the conflict zone was as isolated from the south of the conflict zone as it has been since hostilities began.

At the start of November, the main driver of that isolation was the choking off of the sea route between Palma and Pemba. Between bad weather, overcrowded boats, and the threat of interdiction by insurgent or government ships, moving between southern and northern Cabo Delgado became extremely dangerous. These dangers affected refugees trying to reach safety in Pemba and those who remain in the coastal areas of the conflict zone. News of a shipwreck in which 54 displaced civilians on an overcrowded dhow drowned was reported in November. At least 60 people died of cholera on Ilha Matemo as well, with public health teams unable to reach them due to the security situation.

Then, reports emerged of massacres in Muidumbe district as insurgents took control of a series of towns on the road to Mueda. Boys and adults who had been involved in initiation rites were captured and beheaded, their bodies gathered on a soccer field in Muatide. As news of the killings and insurgents’ threats to extend their offensive reached Mueda, many civilians fled the town, believing it would soon be under siege from the insurgents. Many civilians from Muidumbe and Macomia districts had been living as refugees in Mueda, convinced that the major government security force base there provided a measure of safety. Those refugees, along with many Mueda residents, fled again, mostly to Montepuez, putting a great deal of pressure on humanitarian resources there. The threatened attack on Mueda never came, and a government counteroffensive into Muidumbe relieved some of the pressure, but insurgents are still active in the district.

Mozambique and Tanzania announced a new framework for cooperation in November, papering over an incident in October in which Tanzanian forces launched rockets into Mozambique, injuring civilians. The deal, between the Mozambican and Tanzanian police forces, provides for Tanzania to extradite to Mozambique 516 suspected insurgents it has arrested. Mozambican and Tanzanian police would also undertake joint operations against insurgents. No such operations have yet been reported, but the deal at least signals that tension between the two countries has been reduced somewhat. If joint operations do materialize, they could be a great help to Mozambican forces in Palma and Nangade districts who are not receiving much assistance from Mueda-based troops while Mueda is under threat. On the other hand, given the Tanzanian security forces’ poor human rights record, they might not be very helpful to Mozambican civilians in the area.

In part due to the exodus from Muidumbe, the official count of civilians displaced in Cabo Delgado ticked over 500,000 in November. Despite this, requests from international organizations for assistance in Cabo Delgado continue to be significantly underfunded. Between funding constraints and the slow start of the new Integrated Northern Development Agency (ADIN), the humanitarian outlook in November was distinctly negative.

Child Soldiers

The use of child soldiers in battle has not yet been observed in the Cabo Delgado conflict, but warning signs are there. Back in July, five girls who had been abducted by insurgents during the 27 June attack on Mocimboa da Praia town fled from the camp where they were being held. Once free, they told of men and boys being given military training by the insurgents under heavy security to prevent escape. More recently, a new report claims that “hundreds” of boys are receiving training “far from Mocimboa da Praia.” Other contacts and reporting have mentioned training of children in Mocimboa da Praia. If child soldiers do appear on the battlefield, the long-term damage will be devastating, both in terms of the physical, psychological, and social harm done to the children themselves and the sharp rise in long-term instability that follows a generation exposed to war at a young age. Given these risks, it is important to evaluate the potential for child soldiers to be deployed by the Cabo Delgado insurgency and to understand the aspects of the conflict that, if controlled, could limit the use of child soldiers by the insurgency.

The historical and comparative record on child soldier use in a conflict like the one in Cabo Delgado is mixed. The historic norm against child soldier use in Mozambique is not strong. Both government and RENAMO forces used child soldiers during the civil war, and over a quarter of the fighters formally demobilized after the conflict were children when they were joined up. Given the mixed local and international nature of the insurgency, however, it is not clear how relevant the Mozambican martial tradition is to the insurgents’ decision making.

The Islamic State (IS) may offer some insight, but extenuating circumstances make comparison difficult. Core IS makes frequent use of child soldiers for purposes ranging from propaganda to suicide bombing, but does not require the same of its affiliates. The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), who reportedly make up at least the bulk of the Congo-based contingent of the IS Central African Province (ISCAP), also use child soldiers — indeed, some of them appeared in early ISCAP videos. The ADF’s use of child soldiers, however, far predates the ADF’s relationship with IS.

If we instead compare the Cabo Delgado insurgency to allegedly related Islamist groups in the region, we find a model closer to what has been observed in Cabo Delgado so far. In Tanzania, Islamist militants that many analysts believe have a relationship to the Cabo Delgado insurgency focused on indoctrinating children, but there are no reports of them using children in violent operations. In 2013, Tanzanian authorities found 69 children at an Islamist “child indoctrination camp” in Tanga region. Sources report that Tanzanian authorities also broke up smaller Islamist training facilities for children in 2016 and 2017. This calls to mind the early days of the Cabo Delgado insurgency, before the outbreak of violence, when one of the group’s defining features was its insistence on indoctrinating children in their own madrassas rather than allowing them to attend other schools.

Even if, for now, the indoctrination of children by the insurgency is operating on the Tanzanian model — that is, forced ideological and weapons training, but no clear evidence of deployment — this is only a minor comfort. Assuming the government makes military progress against the insurgency and the group experiences a manpower shortfall, there are few if any normative or practical constraints on the insurgents deploying the children they are training. To impose practical constraints, the leading research on child soldiers suggests three areas of focus: displacement, abduction, and lootable resources.

Internal civilian displacement is strongly associated with child soldier recruitment, both coerced and voluntary. Researchers on the ground in the Democratic Republic of Congo traced this association to insecurity in IDP camps and the ability of militants to move easily among displaced populations. So far, neither of these conditions hold in Mozambique. IDPs who have made it out of the conflict zone to Metuge and points south are relatively safe from insurgents.Insurgents who have tried to infiltrate the camps have been turned over by the civilians with whom they traveled. However, as the insurgents expand the conflict zone to threaten IDP destinations such as Mueda, the risk of forced recruitment of children increases.

Abduction within the conflict zone is another major risk factor, and one immediately relevant to the Cabo Delgado conflict. There are no clear numbers for how many children have been abducted and remain in insurgent custody, but estimates in the high hundreds are reasonable. As displacement has increased and the conflict zone has been depopulated, the dangers of mass abduction have lessened somewhat. However, the ease with which insurgents can reach children in the conflict zone speaks to the core civilian protection issues faced in Cabo Delgado. More than any other factor, the government’s inability to protect civilians from abduction is driving the opportunities insurgents have to utilize child soldiers.

Finally, recent research suggests that rebel groups with access to lootable resources are highly likely to forcibly recruit and deploy child soldiers. The resources serve as both a supply and a demand driver. They drive demand because child labor can be used to exploit resources like gems and timber, and supply because the revenue streams from the resources limit the rebels’ dependence on civilian support to survive, allowing them to abduct children with relative impunity. It is unclear the extent to which those conditions hold in Cabo Delgado. There have been persistent rumors that insurgents control various illicit resource trades in the province — rubies, illegal timber, heroin — but no clear evidence to back up the rumors. Gaining greater understanding of the state of the lootable resource trades in Cabo Delgado could offer insight into the potential roles and demand for child labor in the insurgent war effort.

Militia Update

ACLED records three organized political violence events involving local militias in Cabo Delgado in November, the most of any full month in the conflict so far. Those incidents — all of which took place in Muidumbe district — are the clearest examples of a growing body of evidence that local militias are growing in size, acceptance, and ambition in Cabo Delgado. As discussed in an earlier weekly report, local militias, armed by the Mozambican government but capable of pursuing their own political ends, offer both a challenge and an opportunity for the government in its counterinsurgency effort. The manpower they add could be crucial for the government’s ability to protect civilian populations in the conflict zone. However, adding armed actors makes arranging an eventual peaceful settlement for the conflict more difficult.

As the Mozambican government has increased its support for and reliance on local militias, the pattern of that development has indicated that individual militias are closely linked to Mozambican security force units in their areas. Recently, Mozambican Prime Minister Carlos Agostinho do Rosário met with civilians displaced by the conflict who are living in Metuge and Ancuabe districts. Civilian representatives presented do Rosário with a request for arms so that they could form their own militias and fight against the insurgency. The prime minister turned them down, saying “Firearms should be in the hands of the defence and security people and with the people whom they trust” [emphasis added]. As do Rosário suggests, it is relationships between security force units and militia members that is driving the growth of local militias.

So far, there is clear evidence of militia activity in three districts: Muidumbe, Macomia, and Palma. Of the three, we have the most information about militias operating in Muidumbe. These militias, some of which operate out of Muidumbe and others out of neighboring Mueda district, draw their government support from government security force units based at Mueda. Despite twice being involved in friendly fire incidents with Mozambican security forces during November, the Muidumbe militias have displayed the closest working relationship with government units of any of the local militias. During the government’s mid-November offensive in Muidumbe district, militia members accompanied police forces as they re-occupied the district capital of Namacande.

Indeed, the Muidumbe militias appear to be linked specifically to the police, rather than the military. The connection makes sense, given the police are more ideologically pro-Frelimo than the military and the Muidumbe militias are largely drawn from networks of Frelimo veterans of Mozambique’s civil war. According to a source on the ground in Mueda, the Muidumbe militias are made up of Frelimo loyalists, mostly war veterans, who act out of a mix of patriotism, party loyalty, and desire to protect their homes. They are not paid for their service. Though most are older men (and they are all men in the militias throughout Cabo Delgado), a small number of younger men have also been recruited. If the militia program continues to expand, however, the proportion of younger men involved is likely to increase along with it.

In contrast to Muidumbe, where militias are linked to security force units that take on offensive operations and therefore join those operations themselves, local militias in Macomia district play a more sedentary local security role. The Macomia militias appear to draw their support from the government garrison in the district capital and are limited in their operational area to the west of the district. In the insurgency’s frequent attacks on the district’s eastern Mucojo posto administrativo in recent months, there has been no reported militia response. That tracks with the behavior of the garrison at Macomia, which has been very slow to respond to insurgent operations in Mucojo. Instead, Macomia militias engage in local patrols — including one on 2 December that resulted in a friendly fire incident with a Mozambican military unit which killed multiple soldiers.

Finally, in Palma district, government security forces based in Palma town have been issuing arms to local residents since at least September. Men from across the district — and from near Pundanhar in particular — have been armed and trained, although there has been no definitive evidence yet that they have seen action against the insurgency. Instead, the Palma militias have found themselves, much like Palma civilians, caught between insurgents and government security forces. Insurgents have targeted the homes of militia members in Pundanhar, threatening further retaliation against them and their families for collaborating with the government. Within Palma town, militia members have begun to convey local civilian concerns to their security service sponsors, including lodging a formal complaint on 17 November about looting of civilian property by soldiers in Palma. Given the ongoing tension between civilians and government troops in Palma, the Palma militias seem the most likely to develop into an independent political force.

Ultimately, however, all of these new armed groups complicate the Cabo Delgado political landscape, even as they provide local communities a semblance of security and agency in the conflict. One measure of how complicated things might get — beyond the ongoing problem of friendly fire incidents between militias and government security forces — will be the extent to which militias are able to broaden their recruitment base. Militias that are more reflective of the population, with younger fighters and women among their ranks, will likely have greater capacity for independent political action than militias drawn exclusively from existing Frelimo patrimonial networks.

International Support Update

During November, voices from the region and beyond continued to call for military assistance for Maputo to bolster its efforts to tackle the insurgency. It has now been over six months since the extraordinary Southern African Development Community (SADC) Organ Troika meeting in Harare in May. In a context of worsening security and humanitarian conditions, Botswana, which took over as chair of SADC’s Organ for Politics, Defence and Security from Zimbabwe in August, hosted an extraordinary two-day Troika Summit (26-27 November) in Gaborone to discuss the situations in Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Organ Troika leadership, including the presidents of Zimbabwe and South Africa, were in attendance. President Nyusi was not, instead deploying Defense Minister Jaime Neto to attend in his place. Nyusi’s absence was interpreted by some as a reflection of his lack of interest in expediting a SADC plan of action to assist Mozambique. It was understandably surprising given his attendance at the May summit and significant because Mozambique has been chairing the regional body since August.

Expectations that there would be some concrete developments were thwarted and the frustration of SADC leaders was reflected in the communique released after the meeting in which the Organ “directed the finalisation of a comprehensive regional response and support to the Republic of Mozambique to be considered urgently by the Summit.” No timeframe was imposed in order to avoid imposing a hard deadline on Maputo, but SADC observers noted that the communique’s use of the word “directed” signaled a sense of urgency.

Mozambique has in the meantime continued to explore options for bilateral support from the region and beyond. Bilateral and multilateral approaches need not be mutually exclusive and it is likely that bilateral agreements with key regional states (i.e. South Africa, Angola, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Tanzania) will be fashioned under some form of SADC mandate. The regional body is navigating uncharted terrain, and must find an approach that accords with SADC modalities, accommodates Maputo’s sovereignty concerns, and also deals decisively with the actual security threat in play, which is not limited to Mozambique.

President Nyusi acknowledged in November that he is reaching out across the globe to secure “any kind of support” to build capacity and competency in the fight against terrorism, acknowledging the fight will require external assistance. Mozambique maintains a firm position that it is not looking for a deployment of boots on the ground to assist with the actual fighting, insisting its own forces are capable of doing this. At the same time, it acknowledges more resources and the development of its counterinsurgency capacities are essential. Maputo wants military assistance within the framework of cooperation agreements, a position that was endorsed in November by Mirko Manzoni, the UN Secretary-General’s personal envoy to Mozambique. Reconfiguring and capacitating the security forces while at the same time fighting the insurgency will continue to present major challenges and is likely to temper the speed at which government security forces realize any operational benefit from foreign assistance. It is an approach, however, that the region, however frustrated, is likely to accommodate. How support will be paid for is also likely to remain a critical determining factor.

One area of progress on the bilateral front has been the signing of a Memorandum of Agreement between the police commanders of Tanzania and Mozambique on 20 November in Mtwara, southern Tanzania. This followed a meeting in early November in Dodoma, Tanzania where the re-elected President of Tanzania, John Magufuli, and the Mozambican Prime Minister, Carlos Agostinho do Rosário, met to talk about the importance of bilateral and regional cooperation in combating "terrorism." Although the details of the agreement have not been made public, this is an important step in promised bilateral cooperation between the two countries which is essential for ramping up border security, intelligence cooperation, and efforts to prosecute insurgents. The October attacks in southern Tanzania by Cabo Delgado insurgents appear to have prompted the agreement. The memorandum includes an agreement that Tanzanian authorities will extradite 516 insurgency-related suspects to face the courts in Mozambique. On 26 November, Tanzania’s Inspector General of Police, Simon Sirro, announced they had arrested an unknown number of youth in the western regions of Mwanza and Kigoma who were intent on joining colleagues that had already left to join the insurgency. It is unclear whether and how cooperation might extend to a more practical approach to handling refugees seeking sanctuary in Tanzania. Hundreds looking for safety have been deported back to Mozambique in recent months.

Another area of bilateral progress is between Mozambique and Malawi. Following the resuscitation of Malawi and Mozambique’s Joint Commission for Defence and Security in October (which had been inoperative for over a decade), both countries convened a ministerial level meeting on 20 November that included both Mozambique’s defense and interior ministers. Border security arrangements between the two countries were also strengthened during November with local government agreements signed between the district administrators of Ngaúma, Mecanhelas, and Mandimba on the Mozambican side and the district commissioner of Mangochi, Malawi to combat organised crime and human trafficking.

Meanwhile, progress between Mozambique and the EU on a promised EU aid package remains limited. Despite holding a scheduled bilateral dialogue on 17-18 November that discussed an array of political, economic, and social issues affecting Mozambique, there has been no visible progress in determining what the European Union might be able to bring to the table as part of its promised support for Maputo’s counterinsurgency effort. The EU has already spent €15 million in 2020 on this front, mainly on humanitarian support, and is expected to hold discussions with the authorities based on an assessment of what is requested. No detailed request has been forthcoming, but it is still early days. Reaching an agreement on the substance and conditions of support is likely to take some time, despite some EU member states obviously being keen to expedite the process. On 23 November, Portugal’s defence minister, João Gomes Cravinho, said Portugal was ready to assist; media reports suggest Portugal would send several dozen marines as part of a wider grouping to provide training and advice. Maputo is trying to put in place several initiatives to retrain and resource its beleaguered security forces at the same time as they confront the insurgents. A Portuguese-led effort brings political complications with it, given Mozambique’s colonial history.

Lastly, Saudi Arabia offered its support for Mozambique’s counterinsurgency effort during a two day visit by the Minister of State of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for African Affairs, Ahmad bin Abdulaziz Qattan. Qattan met with President Nyusi on 18 November. The publication Africa Intelligence claims Cabo Delgado’s governor, Valige Tauabo, has been actively lobbying the Saudis to help underwrite Maputo’s fight against the insurgents. According to one source, the basis of a deal might be Saudi financial support for the Mozambican government in exchange for increased Saudi access to the Mozambican fishing industry.