Cabo Ligado Weekly: 13 December- 9 January

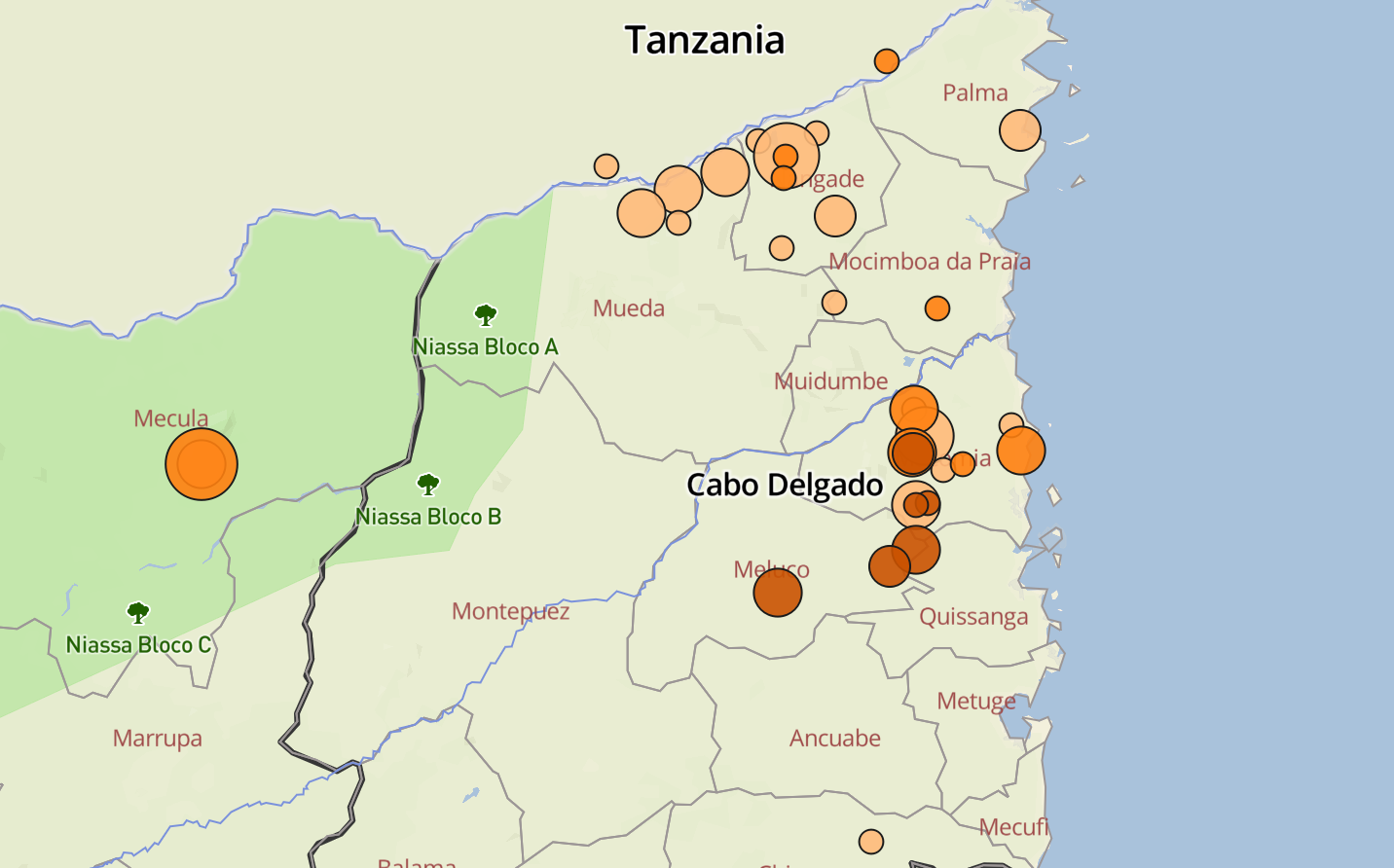

By the Numbers: Cabo Delgado, October 2017-January 2022

Figures updated as of 7 January 2022. Organized political violence includes Battles, Explosions/Remote violence, and Violence against civilians event types. Organized violence targeting civilians includes Explosions/Remote violence and Violence against civilians event types where civilians are targeted. Fatalities for the two categories thus overlap for certain events.

Total number of organized political violence events: 1,111

Total number of reported fatalities from organized political violence: 3,627

Total number of reported fatalities from organized violence targeting civilians: 1,587

All ACLED data are available for download via the data export tool and curated data files.

Situation Summary

The holiday season was bloody in northern Mozambique, with violence continuing in both the southeast and northwest of the conflict zone.

Just before midday on 15 December, insurgents surprised a church pastor and his wife in their fields outside of Nova Zambezia, Macomia district, a village along the N380 roughly 20 kilometers north of Macomia town. The insurgents killed the pastor and beheaded him on the spot, then ordered his wife to bring his head to Mozambican police in Nova Zambezia as a warning. According to one source in the area, the propaganda message the insurgents ordered the woman to convey was that “while you [government forces] are walking on tarred roads, real men [insurgents] are in the woods.” Nova Zambezia had been a frequent site of fighting between insurgents and Mozambican forces in the weeks leading up to the attack.

That line of propaganda has at least two uses for insurgents. First, it indicates the insurgency’s belief in its staying power in Macomia district, a district that mainly falls under the zone of responsibility of the Southern African Development Community’s (SADC) Standby Force Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM). With the SAMIM mandate drawing to a close and extension still unresolved at the time of the incident, the insurgency’s show of strength in Macomia is likely meant in part to intimidate SADC governments about the costs of staying in Mozambique. Second, the content of the message calls to mind the core tactical problem faced by Mozambican and allied forces for the vast majority of the conflict: their ability to operate is severely restricted once they leave main roads because their equipment and training is built around armor rather than infantry or air assault capabilities. By making the case that the tactical dynamic has not changed, the insurgents are arguing to a civilian audience that foreign intervenors have not altered the fundamentals of the conflict despite Rwandan successes in Mocimboa da Praia and Palma districts.

Also on 15 December, according to a claim by the Islamic State (IS), insurgents burned homes and several vehicles in Lichengue, Mecula district, in Niassa province. A local source seemed to suggest that the attack came earlier, reporting that a temporary loss of mobile phone service in the area on 12 December was the result of insurgent action in Lichengue that day. Lichengue sits just five kilometers from the district capital of Mecula, and insurgents had burned over 80 buildings there on 8 December.

On 16 December in nearby Chimene, according to an IS claim, insurgents killed one Mozambican soldier and burned a Mozambican military (FADM) vehicle before burning homes in the village. No independent sources confirmed this claim.

As if to emphasize both of the points from their macabre propaganda statement in Nova Zambezia, insurgents ambushed South African SAMIM forces in the forest east of Chai in northern Macomia district on the night of 19 December. The South African National Defense Forces (SANDF) released a statement saying that one soldier had been shot and killed at the scene. A South African source said that the soldier had been a member of the SANDF special forces, making them the first SANDF special forces soldier killed in combat in 32 years. The same source reported that at least two other special forces soldiers were wounded in the fighting. A subsequent IS claim of the ambush said that two soldiers had been killed, but there is no indication that a second SANDF soldier has died.

The IS claim also, however, included a photograph of the equipment insurgents captured in the ambush that underlined the success of the operation. The equipment includes what appears to be boxes of rifle ammunition, a 60mm mortar round, a number of grenade launcher rounds, and a radio. South African defense expert Darren Olivier speculated that, given the SANDF’s claim that the soldiers were ambushed once on patrol and again at the landing zone for the helicopter sent to extract them, access to the radio may have allowed insurgents to locate the landing zone and set the second ambush.

The targeted SANDF patrol appears to have been part of a larger SAMIM operation that was more effective elsewhere. Mozambican Defense Minister Cristóvão Chume said that a joint Mozambican and SAMIM force attacked an insurgent base somewhere in Macomia district on 19 December, killing 10 insurgents and taking into custody an undisclosed number of women who were found with the insurgents. A subsequent SAMIM statement on the operation offered a fuller accounting, saying that the operation targeted two bases on 19 and 20 December and resulted in the killing of 14 insurgents as well as the liberation of eight women, three children, and two elderly men “believed to have been abducted” by the insurgents. The statement recognized the SANDF losses in the 19 December ambush, saying that one soldier had been killed and two wounded. It also reported that two FADM troops had been killed in the operation and another four injured. In the days after the operation, according to sources, eight insurgents who had been pushed out of their bases by the operation were captured.

On 20 December, police stopped a bus carrying passengers from Nampula to Pemba just outside of Nampula after receiving a tip that a group of passengers refused to open their bags when asked by bus company employees. Police searched the bags, and found firearms. No details have emerged about the extent of the shipment or the types of weapons involved, but one witness reported that the passengers carrying the bags told police as they were being arrested that others had transported weapons along the same route before. The passengers are being held under suspicion that the weapons were meant to be delivered to the insurgency.

On 22 December, insurgents in Niassa province attacked Naulala, Mecula district, where they killed five people, including a ranger of the Niassa Special Reserve, the huge nature reserve that covers much of northeast Niassa province. They kidnapped an unknown number of civilians in the same attack, releasing two women before they left the village. Naulala sits northeast of the district capital on the road to Tanzania, roughly halfway between Mecula town and the Tanzanian border. As they left the village, the insurgents burned two vehicles, including one police truck, on the road south of Naulala.

A man is believed to have been arrested at Mwanza International Airport, in northwestern Tanzania, on 24 December on suspicion of involvement in terrorism. The 37-year-old man was undergoing a standard security check for an evening flight to Dar es Salaam. According to a detailed report and photographs circulating in social media chat groups, the man was carrying the expired Tanzania People’s Defence Force identity card of a man he claimed was his brother, and a small amount of Mozambican currency. Two mobile phones also in his possession contained pictures of battlefield atrocities. Curiously, the lock screen of one device was a picture of Tanzania’s Chief of Defence Forces, General Venance Mabeyo. The man was reportedly taken to Mwanza Central Police Station for further questioning.

With so much conflict-related content in circulation in East Africa, the man may well be innocent of involvement in terrorism, and just unlucky that the airport security check was carried out so diligently. Innocent or guilty, the incident is a reminder that northwest Tanzania remains a critical hub for armed groups operating in Mozambique, as well as Democratic Republic of Congo and Somalia.

Local militia in Nangade district spent their Christmas Day on patrol. On 25 December, Nangade militias captured two suspected insurgents, one each in Ntamba and Litingina. One is Mozambican and the other Tanzanian, and both are entering middle age. The men were fleeing fighting in Macomia, and said they intended to cross into Tanzania. They were malnourished and largely subsisting on dried meat and snails. The men were taken to Nangade town, and eventually transferred to Mueda. A video, purporting to be of their time in Nangade town, shows uniformed men looking on while one of the prisoners is beaten by a man in civilian clothes holding a stick. The video, if authentic, reflects the role local militias play in everyday repression in Cabo Delgado – delivering extrajudicial beatings with the tacit approval of security forces, without those forces having to be directly involved.

Local militias in Macomia acted more clearly in self-defense two days later, on 27 December, when they ambushed a group of 19 insurgents near Chitoio, Macomia district. The insurgent group was reportedly planning to attack the village when militia members attacked them, killing five and capturing one.

On the morning of 27 December, a group of roughly 20 insurgents attacked the village of Alassima, Mecula district. The insurgents killed five civilians and kidnapped seven men and four women before letting the women go with a message threatening security forces. The group also burned a number of homes in the village, which is located just seven kilometers from the district capital.

Though most of the violence in Macomia district is now centered along the N380 corridor in the western part of the district, coastal areas remain contested. On 31 December, insurgents approached a group of fishermen near Olumboa, Macomia district, and demanded that they walk together on the road to help the insurgents avoid suspicion if they came upon a government patrol. One of the fishermen refused, and the insurgents killed him. Presumably, this method of daytime travel along roads will become easier for insurgents to implement as more civilians return to districts like Macomia that were once largely depopulated by the conflict.

Insurgents began 2022 with a return to Nova Zambezia. Early in the morning of 1 January, insurgents entered the village in Macomia district carrying firearms and machetes, surprising residents. They killed three civilians in the attack, all of whom were extended family members of the district administrator of Macomia. IS claimed the incident.

IS also made another claim of an attack on 1 January, saying that insurgents burned homes in “Mbada,” in Macomia district. It appears more likely the group was referring to Imbada, in neighboring Meluco district. There were contemporaneous reports of an attack there, although with few details.

The next day, there was a confirmed insurgent attack in nearby Nangororo, Meluco district, where insurgents looted and burned down a tent. Both Nangororo and Imbada are on the N380, roughly 20 kilometers south of Macomia town. With attacks there and in Nova Zambezia over the same two days, insurgents showed the capacity to bracket Macomia town on both sides of the major road that serves as its connection to both Mueda and Pemba. The same pattern continued for the next several days, which should be a major concern for government security officials going forward. If the insurgency was to make a major push to show that it has retained its offensive capacity, raids on the district capitals of Mecula and Macomia would be the obvious choice. Both now appear eminently feasible for the insurgency.

On 3 January, according to an IS claim, insurgents attacked Nahavara, in northwestern Mueda district. According to the claim, the raiders burned homes and two vehicles. There were reports of violence in Nahavara on 4 January, but it was initially unclear if insurgents or unrelated poachers were the perpetrators. The IS claim suggests that it was an insurgent attack.

Insurgents also returned to Nova Zambezia on 3 January. Entering the village around 2 am, insurgents went from house to house, looting food aid, burning homes, and shooting civilians who tried to resist. In the end, five people were killed and 11 homes burned.

Tightening the aforementioned bracket, insurgents attacked the village of Nova Vida, Macomia district, on 4 January. Nova Vida is also on the N380, about five kilometers closer to Macomia town than Nova Zambezia. Attackers stole food and burned homes.

The same day, insurgents attacked Mariria, Meluco district, a village roughly 15 kilometers west of Imbada. The population fled the village as the afternoon attack began, so there were no casualties. Insurgents looted food in the village and burned homes.

There was another attack in Meluco district on 4 January – in Imbada (again, on the N380.) No other information on the attack is currently available.

Violence in northwestern Cabo Delgado picked up later in the week, beginning with an insurgent attack on Nkonga, in southern Nangade district. Insurgents have a base near the village, from which 24 kidnapped civilians had recently escaped. Insurgents attacked the town on 7 January, killing a local militia member and three civilians.

The same day, insurgents struck nearby Lijungo, also in Nangade district. No details are available regarding the attack.

On 8 January, in northern Mueda district, insurgents attacked the village of Alberto Chipande (known locally as Nachipande), killing two people. One of the victims was a local militia member, and the other was deputy village leader. After the spate of attacks in the north, local sources reported that civilian confidence in SAMIM forces in the area is lower than ever.

New information also came to light during the holidays about earlier incidents in the conflict.

According to an IS claim, insurgents attacked an armored vehicle belonging to the FADM on 3 December in Nalama, Mecula district. The vehicle, IS asserted, was burned and multiple Mozambican soldiers were injured. There are no corroborating reports of an incident at Nalama at that time.

Another IS claim asserted that insurgents burned homes and other buildings in Macalange, Mecula district, on 6 December. There were isolated reports of shooting in Macalange on 3 December.

On 12 December, a group of three insurgents canoed from the mainland to Ilha Magundula, off the coast of Macomia district, and captured a group of fishermen there. The fishermen made an escape attempt and, in the ensuing struggle, at least two of them were injured. The insurgents then looted the food available on the island and returned to the mainland. The injured fishermen are recovering in Pemba.

A new report also came out during the holiday that offers an overview of the arsenal the insurgency has built up over its four year existence. Drawing on photos and videos of insurgent weapons released both by IS and by pro-government forces, the report contains granular detail on what kinds of arms and munitions to which the insurgency has access. The report’s main conclusion is that the insurgency draws its weapons from its foes, and has done so quite successfully. The weapons on hand are all found in Mozambican (and/or Tanzanian) state security force armories, and there is little evidence that the insurgency receives weapons from foreign suppliers. Capturing weapons has not only kept the insurgency fairly well stocked with rifles and bullets, but photo evidence shows a small but steady stream of 60mm and 81/82mm mortar shells entering their arsenal. If an improvised explosive device program ever becomes a major part of the insurgent strategy, those shells will likely become a major factor in the conflict.

The holiday also brought another account of conditions in insurgent camps from two women who escaped insurgent custody on 22 December. The two had been held by insurgents near the Messalo River for nearly two years. The most notable part of their account is their contention that many civilians held by the insurgents have been killed in operations by pro-government forces because insurgents are using them as human shields. There has been little direct evidence of human shield use during combat by insurgents, but with so much of the fighting between insurgents and pro-government forces in recent months taking place in the bush and away from the press and other observers, it is possible that human shields are being used and then their deaths are being included in pro-government accounts of insurgents killed.

Incident Focus: Niassa Conservation Under Threat

The conflict in northern Mozambique is most often discussed in relation to the threat it poses to natural gas development in Cabo Delgado province, on which so much of Mozambique’s national economic plans depend. Yet, as the conflict becomes more deeply embedded in northeast Niassa province, it is beginning to threaten another national goal and source of economic growth: conservation. The insurgent attacks in Mecula district have all taken place within the Niassa Special Reserve, a nature reserve that makes up 31% of Mozambique’s protected land and is home to 42 villages and a major elephant population. As violence in the reserve increases, it threatens to overturn both the conservation gains that have been made in the area and the delicate economic balance that preserves them.

Recent articles in Carta de Moçambique and the Daily Maverick have made a compelling case for the environmental and economic costs of fighting a war in a nature preserve. Insurgents and displaced civilians living in the bush have strong incentives to hunt whatever they can find for food, regardless of their prey’s protected status. Displacement destroys peoples’ livelihoods, leaving them more open to the lure of poaching. The local people who have built up the most conservation expertise over the years of the Reserve’s existence are among those most likely to have the resources to flee the violence, leaving the reserve to start from scratch even after the fighting is over.

Yet recent events suggest that the conflict poses an even more direct threat to the Reserve and the economy that surrounds it. It appears that insurgents have begun to target conservation workers in their attacks, perhaps categorizing them as being agents of the state in the same way that teachers or local village chiefs have drawn the insurgents’ ire. As noted above, a ranger for the reserve was among those executed in the 22 December attack on Naulala. In addition, of the two vehicles that were burned in the aftermath of that attack, one was a police truck and the other belonged to a private conservancy that works within the reserve.

If conservation workers are treated by the insurgency as state actors, then the threat the conflict poses to the future of the Niassa Special Reserve may be greater than the one it poses to natural gas development in Cabo Delgado. Neither the Mozambican government nor foreign intervenors are likely to step in to save the reserve, and the potential for damage to its key infrastructure, both human and natural, is significant.

Government Response

For all of the ways that civilian life in Cabo Delgado has become more normalized in the months since pro-government forces regained control of Mocimboa da Praia, one thing that has not changed is the centrality of state security forces to any form of civilian economic activity. Travel between Mueda and Palma by way of Mocimboa da Praia, for example, remains strictly regulated, with the Mozambican security forces conducting more or less regular convoys along the route. According to a source who saw the start of a convoy in Mueda, the route has become a source of revenue for the officials in charge of managing it. The source reports that the convoy escorts accepted payment of between 4,000 and 5,000 meticais ($63 and $78, respectively) per vehicle for a service that is notionally supposed to be free. Likely as a result of the extra cost, bus fare along the route has jumped over fourfold, from 350 meticais ($5.50) to 1,500 meticais ($23.50).

In a similar vein, security forces continue to assert their role in deciding when displaced civilians will be allowed to return to their home communities in the conflict zone. The Cabo Delgado provincial police commander declared in late December that people attempting to move back to Palma, where security and economic conditions have improved significantly in recent months, must register beforehand in order to prevent insurgent infiltration. Yet it seems as though he was more focused on the problem of managing access to Palma’s economic output (arguably one of the core issues of the entire conflict) than on preventing insurgent infiltration, noting that “we have populations coming from Balama, Montepuez saying they want to ‘return’ to Palma district” for access to economic opportunities. It appears that management of access to Palma will remain a major security force activity for some time to come.

For people in Palma, however, who were displaced from Mocimboa da Praia, there are now indications that they may soon be allowed to return to Mocimboa da Praia town. In early January, displaced civilians from Mocimboa da Praia living in Palma and nearby Quitunda were told to expect a religious ceremony in coming weeks that will signal the opening of Mocimboa da Praia town, at which point they can begin to go back to their homes. Mocimboa da Praia has been basically empty as Mozambican and Rwandan troops have been searching it for insurgents, intelligence, and booby traps since it came back under government control in August of last year.

For civilians living further south, reconstruction efforts are yielding mixed results. On the positive side of the ledger, the government inaugurated a new metal bridge over the Messalo River in Montepuez district on 22 December. The bridge will allow for easier travel, especially during the rainy season, for people wishing to get from Montepuez and Pemba to Mueda without traveling through the conflict zone.

On the negative side of the ledger, however, is the ongoing water crises facing Mueda and, to a lesser extent, Montepuez districts. In Mueda, pressure on water resources brought on by population increases as a result of mass displacement has left many wells dry. Water prices are up to between 100 and 150 meticais ($1.50 to $2.40) per 20 liter bucket, a price which is unsustainable for the vast majority of civilians in the area. In Montepuez, the boreholes dug to serve displaced populations are also straining to produce enough water, and some report that the water they do get is sometimes salty.

In Metuge district, conditions in the Taratara relocation site for displaced people are so bad that a mass movement to return home has begun. Many families staying in Taratara hail from Quissanga district, and roughly 20% of the 548 families living at the site chose to return there close to the new year. The remaining families are threatening to join them if their food needs are not met. They complain that they have not received food assistance for three months. As the rainy season begins in earnest, this kind of emptying out of relocation sites is exactly the kind of danger posed by the international community’s failure to adequately fund food aid in Cabo Delgado. Though Quissanga has been relatively safe recently, new attacks in nearby Meluco district suggest that civilians returning there are still under threat of insurgent coercion. By creating a situation where people have to return to their fields to attain an acceptable level of food security, the international community has increased those people’s vulnerability to the conflict.

One response to the lack of external food aid has been to encourage displaced people to take up farming in their new communities outside the conflict zone. Distribution of agricultural inputs to displaced people continued in December, with displaced people at the Corrane relocation site in Nampula province receiving some 180 tons of agriculture kits. The inputs are meant to serve 2,900 producers, which is interesting given that, by the humanitarian community’s most recent count, there are only about 2,100 adults in total living at Corrane. The added inputs might suggest an effort to improve relations between displaced people and host communities by ensuring that farmers in host communities also receive some assistance. Indeed, at the distribution ceremony, Nampula Secretary of State Mety Gondola told displaced farmers that “these few supplies cannot be a factor for there to be division and confusion there in the community. We appeal to us to be together and in harmony to overcome our difficulties.”

For the newly displaced as a result of violence in Niassa province, hasty arrangements are being made. Niassa Secretary of State Dinis Vilanculos told reporters in early January that there are 3,803 displaced people living in a school in Mecula town, and that those people will be relocated to an area outside the provincial capital of Lichinga. Some, however, have decided that Lichinga is not far enough and have reportedly entered neighboring Malawi to live as refugees. Malawi has a long history of taking on refugees from Mozambican conflicts, and the Malawian government is mobilizing to understand the extent to which history may repeat itself as the conflict grows in Niassa.

Elsewhere on the international front, on 20 December, the leaders of the Mozambican and Tanzanian security services met in Cabo Delgado to discuss further cooperation between the two countries. The meeting was notable for two reasons. First, it included both military and police officials from both sides – an expression of unity of purpose between the military and police that is rare in Mozambique. Second, according to a press statement by FADM Chief of Staff Joaquim Mangrasse, the meeting was aimed at improving cooperation to “bring terrorism within the scope of bilateral relations.” No SAMIM extension had been agreed at the time of the meeting, so one way to read it is as part of a long-term attempt to decouple Mozambique-Tanzania security cooperation from a regional framework.

An extension agreement for SAMIM has been reached since (and will be covered in depth in the next Cabo Ligado weekly), but the summit to discuss the extension was postponed following a surprise meeting between the Mozambican and Rwandan governments. Rwanda and Mozambican top defence and police chiefs met at Rwandan National Police headquarters in Kigali on 9-10 January, reportedly agreeing to extend Rwanda’s role in security sector reform initiatives and the broader stabilisation of Cabo Delgado. The agreement provides for the creation of ‘joint security teams’ to encourage cooperation between Mozambican and Rwandan forces in Cabo Delgado. The meeting was part of a three day visit by Mangrasse and Mozambican police chief Bernardino Rafael. Details of the agreement, which was signed on 11 January, are not available. The apparent absence of SAMIM observers at the Kigali meeting raises questions about Mozambique’s commitment to promoting collaboration between SADC forces and Rwanda.

In assistance from further afield, the Indian government in late December donated two Fast Interceptor Craft to the Mozambican navy to assist with efforts to interdict insurgents along the Cabo Delgado coast. The ships are similar to the DV15 patrol craft already in service in the Mozambican navy.

© 2022 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.