Cabo Ligado Weekly: 18-24 October

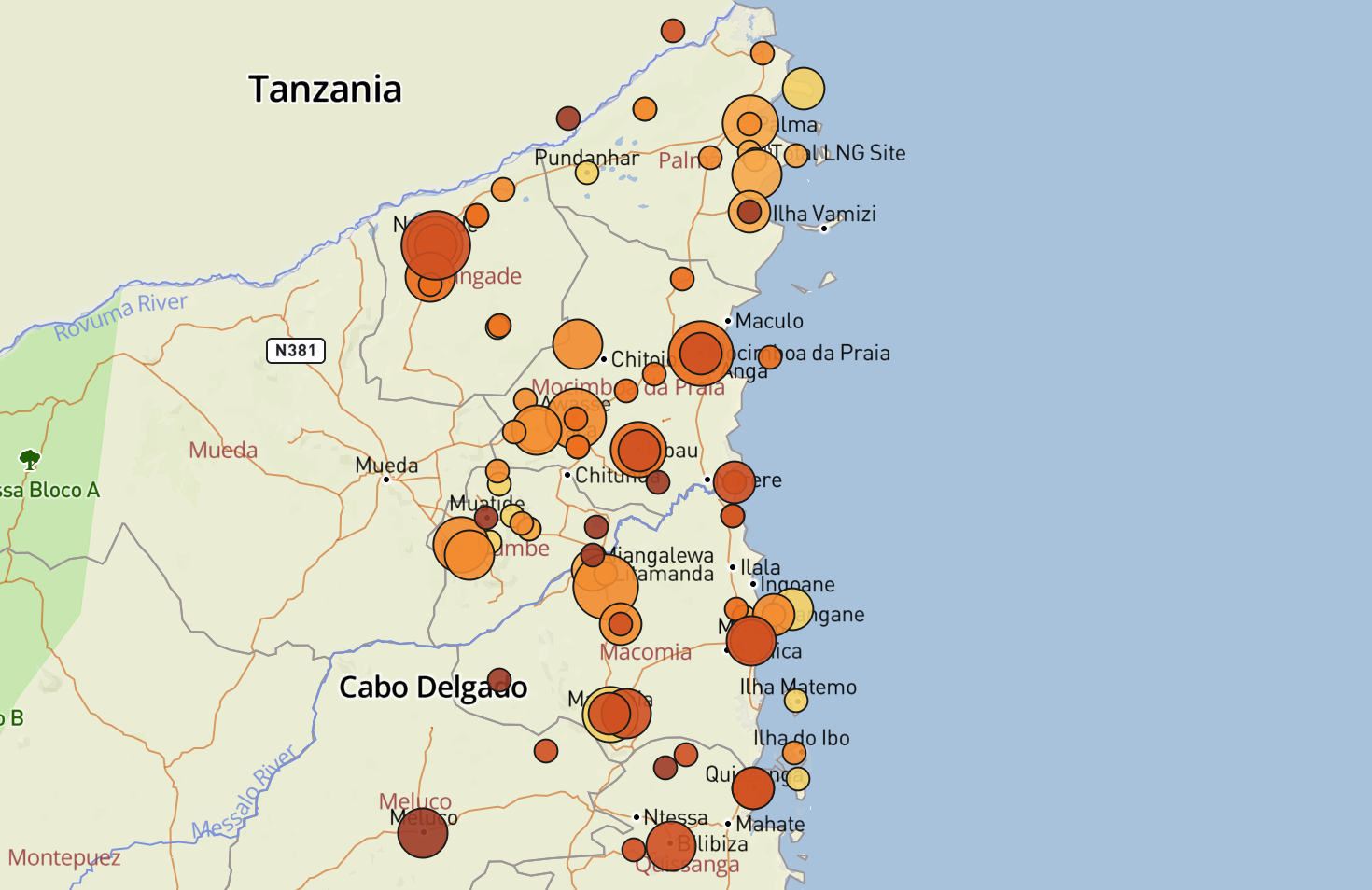

By the Numbers: Cabo Delgado, October 2017-October 2021

Figures updated as of 22 October 2021.

Total number of organized political violence events: 1,029

Total number of reported fatalities from organized political violence: 3,415

Total number of reported fatalities from civilian targeting: 1,538

All ACLED data are available for download via the data export tool and curated data files.

Situation Summary

Insurgents returned to Tanzania last week, their second confirmed incursion in October. On the night of 20 October, insurgents entered Kilimahewa, a village in the Tandahimba district of Mtwara region, north of Cabo Delgado’s Nangade district. The insurgents burned down a cashew nut warehouse in the village and captured an unknown number of civilians. The next day, a Tanzanian military detachment arrived from an encampment about 25 kilometers away and freed the hostages. It is unclear if any casualties resulted from the incident. The warehouse belonged to a Tanzanian cashew plantation owner, and the Tanzanian military has recently been involved in regulating the cashew trade to prevent cross-border transactions. Still, though, there is a strong possibility that the warehouse contained at least some Mozambican product. Southern Tanzania has become an even more important export hub for Mozambican cashew producers since the conflict in Cabo Delgado began, as many Mozambican cashew processing and storage facilities have been rendered unusable by the violence.

Insurgent violence also resumed in coastal Macomia district. On 22 October, a group of five civilians who had crossed into Macomia district from Ilha Matemo in search of fresh water were set upon by insurgents. The attack took place at a well in Lumumua (possibly Olumbua), on the coast near Mucojo. The insurgents beheaded two of the civilians; the other three were able to escape. According to another report, insurgents also beheaded two other civilians near Mucojo between 21 and 22 October. The beheadings represent a return to the kinds of attacks common in August and early September in which civilians attempting to access natural resources on the Macomia coast ran afoul of small groups of insurgents in the area. Many of the insurgents appeared to be in transit following joint Rwandan-Mozambican operations that uprooted many insurgents in Mocimboa da Praia district.

In Nangade, civilians attempting to return to their village in the eastern part of the district to harvest cashews were attacked by insurgents on 24 October. Insurgents infiltrated the village of Chitama and killed three people -- two local militia members and a community leader. The insurgents also kidnapped three women, forcing them to carry bundles of cashew nuts before letting them go.

In Palma district, Rwandan forces spent last week opening their medical facilities to civilians. Rwandan military doctors treated 184 civilians, for health issues ranging from malnutrition to skin infections. The medical care was provided in Quiwiya, Quilinde, and Quionga, reflecting increased levels of security in the northeast of the district.

Incident Focus: Arrests in Mocimboa da Praia Choke Commerce

New information arose last week about earlier arrests in Mocimboa da Praia, adding context to the public understanding of the situation there as increasing numbers of civilians return home to conflict-affected districts. Sometime between 13 and 15 October, two traders were arrested at sea as they were passing by Mocimboa da Praia with about $6,200 worth of goods. The traders told Mozambican authorities that they were coming from Pemba and intended to sell the goods in Palma, where civilian markets have sprung back into life as the security situation has stabilized. Mozambican police, however, detained the men anyway, accusing them of transporting goods to the insurgency. They were among 150 people arrested in ocean sweeps during that period, in which Mozambican authorities interdicted three ships off of Mocimboa da Praia.

The 150 arrests are part of a wider pattern in Mocimboa da Praia. On 10 October, authorities there arrested 60 people at sea attempting to travel from Ilha Matemo to Palma. Mozambican police then arrested a local leader on Ilha Matemo for allowing the people to leave. Between 6 and 8 October, authorities captured seven boats off the Mocimboa da Praia coast, arresting an unknown number of crew and passengers. The boats were carrying supplies from Pemba to Palma. On 13 September, the Mozambican Navy captured 20 men off the coast of Mocimboa da Praia, accusing them of being insurgents. The men protested that they were actually civilians heading for Palma.

The government contends that each of these arrests prevented shipments of supplies and recruits to the insurgency, but the government’s contention that these large shipments were bound for insurgents is unfounded. Accepting delivery of shipments of the size described by authorities would require significant insurgent manpower and storage capacity, both of which are in short supply in coastal areas. By the government’s own reckoning, pro-government forces have cleared all of the major insurgent bases that might have been used to store large shipments.

Furthermore, the story told by civilian witnesses to the arrests is remarkably consistent. Across each of these cases, the evidence suggests that the people arrested were attempting to engage in the return of commerce to coastal Cabo Delgado, transporting supplies to areas where they are needed. Some sources suggest that Mozambican authorities are aware that those arrested are innocent traders and are simply demanding payoffs to allow trade between Pemba and Palma to continue. Past behavior by Mozambican forces, including extortion and stealing, lends credence to these allegations, as does the fact that all safe routes between Pemba and Palma run either through Mocimboa da Praia or along its coastline, creating a tantalizing choke point for profit-seeking security officials.

Beyond the threat to traders and other passengers, the frequent interdiction of trade between Pemba and Palma poses a real problem for displaced civilians attempting to return to their homes in northeastern Cabo Delgado. As noted in the most recent Cabo Ligado Monthly Report, the race is on for displaced farmers to get home and begin planting before the rainy season begins, in order to achieve a level of nutritional self-sufficiency when harvest time comes. Even for people who succeed in getting their fields into production, however, finding enough food for the next five months is likely to be very difficult. The World Food Programme (WFP), which has already been providing half-rations of food aid for displaced people in Cabo Delgado since July, announced last week that it will have to continue cutting back on food distribution due to lack of funding from international partners. The cutbacks are already being keenly felt in resettlement camps outside the conflict zone, and, though WFP has begun to offer food aid in Palma district, will likely make efforts to extend aid into other conflict-affected districts more difficult.

In the absence of international aid, the major source of food and other crucial supplies for those attempting to rebuild their lives in conflict-affected districts will be local traders. Their ability to move food between different parts of Mozambique -- and perhaps even to import it from Tanzania -- could provide a bulwark against starvation in areas underserved by aid. Yet frequent interdiction of local traders at the choke point at Mocimboa da Praia could increase the cost of servicing conflict-affected districts in the northeast so much that any nutrition gains offered by local traders would be wiped out. The ease of transit through Mocimboa da Praia will be a major indicator of trading networks’ ability to serve returning civilians between now and harvest season.

Government Response

Despite the food pressures displaced people will likely face when they return home, conditions for displaced people on the edges of the conflict zone make the prospect seem enticing to many. In Pemba, for example, mass displacement has led to widespread overcrowding in the city. Between 2018 and 2021, the city’s population doubled, from 200,000 people to 400,000. The increase means that housing remains at a premium and that many people are forced to live in close quarters, despite COVID-19 concerns. It has also led to increased crime, especially in neighborhoods with high numbers of displaced people who are particularly vulnerable to criminal gangs. People complain in particular of high numbers of muggings and home robberies.

For displaced people living in more rural areas, access to good land is a major mediator in their desire to return home before the rainy season begins. Roughly 1,000 displaced people in the Mavala area of Balama district report that their agricultural efforts there are coming along so well that they may not return home in the near future. In Nangade district, however, displaced people who have tried farming in Mecubri report being eager to return to Mocimboa da Praia district as soon as it is possible, believing that the move will bring them greater economic security than remaining in Mecubri.

Though returns to Mocimboa da Praia are still few and far between, the process of returning to Muidumbe district is well underway. Frelimo party officials were in Miteda, Muidumbe district on 21 October to distribute 20 tons of food and other supplies to returning citizens. The party’s first secretary for Cabo Delgado made a speech at the event imploring the first round of returnees not to loot from their neighbors’ homes -- a problem that will likely grow in scope as returns increase.

On the international front, the World Bank pledged an additional $100 million to reconstructing Cabo Delgado last week. The grant joins another $100 million grant made by the World Bank last year to support the work of the Northern Integrated Development Agency (ADIN). It is not clear if the new grant will also be administered through ADIN. The World Bank said that it hopes the money will be used to rebuild public infrastructure in conflict-affected areas and offer psychosocial support to displaced people traumatized by the conflict.

The US government announced its own set of programs for Cabo Delgado last week, aimed at improving youth employment in the province. The programs, which will receive $7 million in US funding over the next three years, appear designed in part to prevent further insurgent recruitment of young people by getting them access to other forms of employment. That approach dovetails with the course ADIN has chosen to address the conflict, which emphasizes youth economic empowerment as a way to prevent radicalization. Though there is evidence to suggest that some insurgent recruitment was at least in part the result of economic incentives, it is also well documented that early insurgent leaders were successful local traders -- among the most economically empowered youth in the region.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.