Cabo Ligado Monthly: December 2022

December At A Glance

Vital Stats

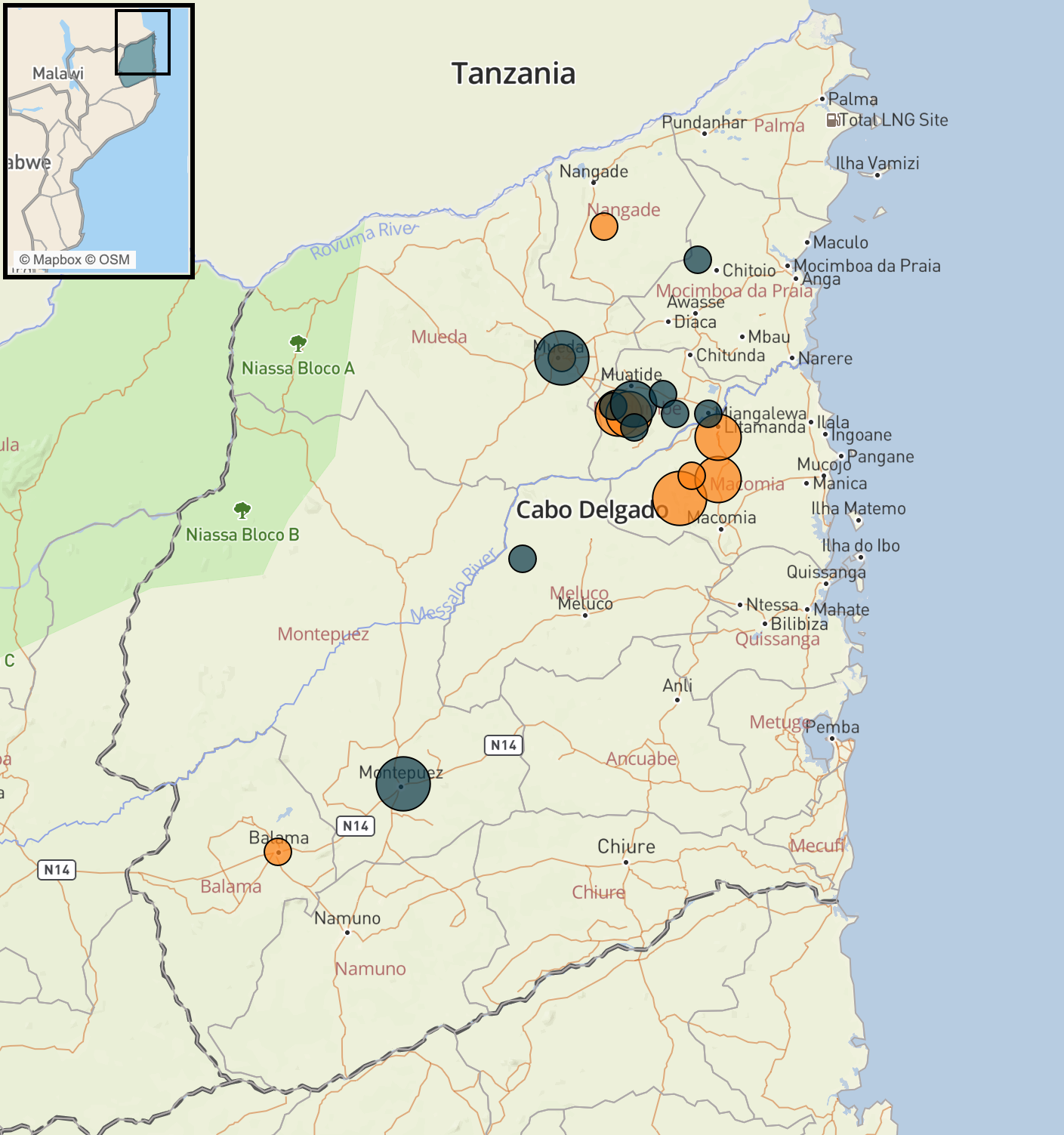

ACLED records 31 political violence events in Cabo Delgado province in December, resulting in 64 reported fatalities

Reported fatalities were highest in Muidumbe district, where insurgents clashed with the Muidumbe communal militia and attacked civilians

Other events took place in Macomia, Mueda, Montepuez, Nangade, Balama, Meluco, and Mocímboa da Praia

Vital Trends

Insurgent activity centered on Macomia and Muidumbe districts

Return to Mocímboa da Praia was sustained over the month

A legislative amendment was adopted to bring Local Forces under the purview of the army

In This Report

The risks and challenges of legalizing Local Forces

Displacement and return at the end of year

Cabo Delgado – on the road to stability?

Palma is back, Mocímboa da Praia next

December Situation Summary

Political violence events occurred in nine of Cabo Delgado’s 17 districts in December. There was a slight decrease in the number of political violence events, with 31 events recorded in December, compared to 38 in November. There was a steeper decline in reported fatalities, from 91 to 64. The concentration of incidents last month was in Macomia and Muidumbe districts.

In Macomia district, there were a number of clashes between insurgents and security forces, as well as attacks on civilians by insurgents. These events were centered on four villages in the north of the district: Nguida, Nkoe, Chai, and Novo Zambézia. Nguida has been under consistent attack from insurgents since October, and since November 2022, insurgents and the Mozambique Defense Armed Forces (FADM) have vied for control of the deserted village. On 6 December, FADM withdrew from their outpost in the village as it was taken by insurgents. This was the seventh political violence incident there since October. There were two subsequent attempts to retake Nguida, on 9 and 12 December. The latter effort was successful.

The villages of Nkoe and Novo Zambézia were the scene of clashes between Defense and Security Forces (FDS) and Local Forces and insurgents, as well as attacks on civilians on 12 December. Over a week later, around 21 December, Local Forces clashed with insurgents at Novo Zambézia.

The second half of the month was dominated by incidents in Muidumbe district. The year ended with a series of clashes on 30 and 31 December between Local Forces and insurgents in the adjacent villages of Namacule, Nampanha, and Namande. A legislative amendment bringing Local Forces under the command of FADM is hoped to strengthen their position in the conflict.

The sustained return of displaced people over the month to Mocímboa da Praia was the most positive development. Over 800 individuals returned between 30 November and 27 December, according to International Organization for Migration (IOM) data for that period.

The Risks and Challenges of Legalizing Local Forces

By Tomás Queface, Cabo Ligado

On 15 December 2022, the Mozambican parliament approved an amendment to the 2019 legislation governing the FDS to grant legal status to communal militias, commonly known as Local Forces. With this amendment, Local Forces are no longer regarded as non-state actors but operate within a specific legal framework, and with a defined command structure, albeit for a temporary period, according to the minister of defense. While these forces have been important actors in protecting communities against insurgent attacks in Cabo Delgado, their legalization carries a number of risks and challenges for the government.

The legalization of Local Forces has always been an objective of the government, and the Frelimo party in particular. In April last year, speaking at the sixth National Conference of the Association of Combatants of the National Liberation Struggle (ACLIN), an important Frelimo body, President Filipe Nyusi praised the role of the communal militias, who, according to him, “have contributed to putting an end to the injustices and heinous crimes perpetrated by terrorists.” These words were echoed by General Commander of the Police Bernardino Rafael who called on people not to flee from insurgents, but rather to stay and protect their villages with the resources at their disposal. Minister for National Defense Cristóvão Chume has driven the process. Upon taking office, Chume was given the mission of modernizing the FDS. Speaking in April 2022, he said the ministry was working on a statute to ensure that Local Forces “continue to work in alignment” with the government, and “continue to respect human rights.”

To enable the legalization of Local Forces, the Mozambican government submitted an amendment to article 7 of the Law on National Defense and Armed Forces of Mozambique – Law 18/2019 of 24 September – in order to incorporate Local Forces within the FADM structure. The law has always recognized the role of citizens in national defense. Prior to the amendment, paragraph one of the aforementioned article stated: “The defense of the homeland is the fundamental duty of all Mozambicans.” The law did not allow for local militias to be operational, and civilians were incorporated into the defense forces through military service, which is also regulated by law. The military service establishes the military registration of citizens as a way for them to join the FADM. On the other hand, the law also foresees the mobilization of civilians (in general or in part) for the defense of the homeland. However, this mobilization is made in the context of war, according to article 161 of the constitution, and such a declaration has not yet been made in Cabo Delgado.

The incorporation of Local Forces into the FADM, rather than the police, is justified on the basis of Article 8 of the Defense and Security Policy, which states that “within the scope of the implementation of the Defense and Security Policy, the Ministry of National Defense shall be responsible for providing the framework for citizens to fulfill their duty towards national defense, in accordance with the law.”

In this context, the Mozambican parliament approved the addition of the following paragraphs to article 7 of the Law on National Defense and Armed Forces of Mozambique:

The passage to active and passive resistance of citizens in areas of the national territory occupied by aggressor forces may be materialized through the Local Force, comprising the community members of a basic territorial circumscription.

The Local Forces shall function under the direction of the General Staff of the Armed Forces for the Defense of Mozambique;

The establishment, organization, and functioning of the Local Force is the responsibility of the Council of Ministers.

In Chume’s perspective, the legalization of Local Forces is intended to “strengthen the role of the FDS in combating and containing the spread of terrorist incursions, protection of community settlements and public and private infrastructure.” To put it another way, Local Forces are expected to fill the gap left by the FDS, given its limited local knowledge. Estimates indicate that the FADM, for example, has just under 12,000 active personnel throughout the country, which is insignificant to guarantee sufficient protection of the whole country, not to mention the 17 districts of Cabo Delgado.

A regulation yet to be approved by the government will shed more light on the establishment, organization, functioning, and timeframe of Local Forces. Currently, Local Forces emerge spontaneously, or at the behest of the government or even of political parties. A recent example is the case of the Naparama militia, who were encouraged by the Frelimo secretary in Cabo Delgado to take an active role in the conflict, by setting up checkpoints on the main access roads and carrying out patrol operations. The regulation to be approved by the Council of Ministers should also clarify the limits of action by Local Forces, both from an operational and timeframe perspective.

The approval of this law was not by consensus in the Mozambican parliament. The opposition parties RENAMO and Movimento Democrático de Moçambique (MDM) voted against the bill, firstly on the grounds of the lack of clarity about the profile of the citizens who will make up Local Forces and benefit from the weapons, and secondly, the risk of proliferation of arms. MDM suggested that the protection of community settlements and public infrastructures should be guaranteed solely by state forces, rather than by community forces. FRELIMO proposed to legalize Local Forces as a temporary and transitional force to be used in the context of Cabo Delgado’s conflict.

The establishment of Local Forces will bring challenges. On the political side, the existence of militias may pose a threat in the post-conflict era, considering how complicated the disarmament and demobilization process of former combatants is. To avoid this, these forces will have to break away from their party alignments, if a wholly non-partisan defense sector is to be developed. Most members of Local Forces are affiliated with the ACLIN, a Frelimo party organization that brings together veterans of Mozambique's liberation war. Their close ties to the party may, in future circumstances, transform them into an armed wing of the Frelimo party, as the country seeks to rid itself of armed political parties.

From a military point of view, Local Forces operate under their own, and sometimes autonomous from the FDS, command. Although political rhetoric claims that these two forces work in coordination, their relationship on the ground has been mixed. At times it is marked by coordination, and at other times by disputes. While the FDS accuses Local Forces of being inexperienced in combat and of hindering counterinsurgency efforts, the latter criticize the FADM and police for not being effective in combating the insurgency. A challenge facing the Ministry of National Defense, and the FADM in particular, is how to build a hierarchical relationship between forces that have at times been at odds with each other. There is already an effort by the provincial government to impose this hierarchy. In his last trip to Montepuez on 9 January 2022, provincial Governor of Cabo Delgado Valige Tauabo sought to make it clear to the Naparama that the FDS is leading the counterinsurgency efforts, and that they should be fully subordinate to its command, acting in a concerted and coordinated effort to achieve success.

A further challenge is accountability for the actions taken by Local Forces. The mechanisms that the FADM will put in place to monitor and hold Local Forces accountable for practices that violate human rights are not yet in place. Several cases of military abuses have already come to light in the media, without the FADM announcing any kind of investigation or holding anyone to account.

On the material side, Local Forces do not receive any military training. From the government, they receive only ammunition, uniforms, and food. They do not receive salaries, though as war veterans, some receive pensions through the Ministry of Combatants, which serves as a kind of incentive. The Naparama forces, a distinct group of local militias, receive no material incentive. The Ministry of National Defense should establish criteria for payment and other incentives for Local Forces. If it decides to provide salaries, many citizens may join Local Forces as a means of earning income as a strategy to escape unemployment. If not, it is possible that the allocated weapons, if not properly monitored, could be used to commit crimes.

The Mozambican government believes that Local Forces will address the manpower deficit of the FDS and thus ensure the security of villages and towns. However, the challenges presented here may pose a potential threat in the near future. The regulation governing Local Forces may address some of them, but it is certain that the country will still face the problem of armed militias for some years to come.

Displacement and Return at the End of Year

By Peter Bofin, Cabo Ligado

There are some clear patterns in the data gathered by the IOM. Firstly, and obviously, displacement is being driven by patterns of conflict. However, there is evidence that in December, military operations against the insurgents may have driven considerable displacement. Secondly, people returning to their places of origin account for between 20 and 30% of those on the move. Most of that traffic is from Montepuez to Mocímboa da Praia. Thirdly, most of those displaced have been displaced more than once, some up to four times and more. These patterns highlight critical issues for the military and humanitarian response to the insurgency.

IOM records arrivals, departures, and returns across Cabo Delgado and neighboring provinces. For the first three weeks of December 2022, displacement was concentrated in the north, where 934 arrivals were recorded in Mueda district. The bulk of these were people coming from the districts of Nangade, to the east, and Muidumbe, to the south.

People flee for fear of attacks, as much as in response to direct attacks. This may explain the numbers fleeing from Nangade district in December. FADM and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) started operations there in late November, targeting bases in the Nkonga area, operations in which SAMIM lost two troops. SAMIM claimed to have killed 30 insurgents in those operations, claims that were later seen to be close to the truth.

Sightings of insurgents moving through the district in small groups in response to these attacks are not surprising. Cabo Ligado has been informed of two such sightings in mid-December. The first was near Nkonga, and the second closer to Nangade district headquarters. Also, in the middle of the month, SAMIM troops from the Tanzania contingent killed a motorcyclist active in smuggling fighters across the border. The combination of concentrated FADM and SADC operations, including the movement of troops by helicopter, and insurgent dispersal in response, is likely to have triggered population movements. It is not clear if the sharp decline in movements in the fourth week indicates a lessening of counterinsurgency operations in the district.

Reasons for movement out of Muidumbe are also, of course, conflict-related, but arising more from insurgents’ actions, and not necessarily actions in Muidumbe only. ACLED data show two attacks in Muidumbe district that likely precipitated displacement seen in December. On 28 November, there was a clash at Miangelewa near the border with Macomia district. Islamic State (IS) claimed the attack, and the killings of five soldiers as well as the seizure of arms and ammunition. The only incident in the first two weeks of December in Muidumbe was the beheading of a man in Muambula. The potential impact of such attacks on the population should not be underestimated. As IS pointed out in al-Naba in November, the killing of just one can be “sufficient to displace hundreds of Christians in the neighboring villages.”

There was, however, quite intense insurgent activity in the north of Macomia in areas bordering Muidumbe in the first three weeks of December. Between 5 and 11 December, there were repeated clashes between insurgents and joint FADM/SAMIM forces at Nguida, just 20 km south of the Messalo river, which marks the border with Muidumbe. Between 11 and 21 December, there were clashes with FADM and attacks on civilians in Chai and Nova Zambézia villages, further north and closer to the Messalo river. Though quite depopulated due to the conflict, remaining residents wishing to flee could easily cross the Messalo river bed, which was dry at the time.

There is a risk that operations in January on either side of the Messalo river in Muidumbe and Macomia, branded as Operation Vulcão IV, may be followed by the type of secondary displacement seen in Nangade. The disruption of insurgent bases will cause them to move, and induce fear of attack amongst the population in a wider area.

The other notable trend in December was the sustained return of displaced people from Montepuez to Mocímboa da Praia. IOM data shows that 1,867 people returned from Montepuez to their place of origin between 30 November and 27 January. Of those, at the very least, 826 returned to Mocímboa da Praia. The place of origin for returns from Montepuez in the second week of December was not reported. Given that the vast majority of returnees in other weeks were making their way to Mocímboa da Praia, we can assume that to have also been the case for that week.

The steady return to Mocímboa da Praia seems to be a response to incentives. Return from Palma was initially supported by Rwandan intervention forces in June last year, but has been more widely promoted since August 2022. Medical services are improving: Doctors Without Borders resumed operations in the town in September, and has opened a 16-bed health facility in the town. The government is reportedly distributing seeds to returnees for planting. A humanitarian source has told Cabo Ligado of improved food aid in the town. However, there are other factors, such as inadequate food aid, lack of land for subsistence farming, and conflicts with host communities, which drive people away from displacement centers.

Perhaps the most striking figure from IOM data is how many people continue to be forced to move by the conflict, not for just the first time but sometimes for the fourth or more times. In the first week of December, 68% of those displaced were on the move for the third time or more. This pattern has been consistent throughout the conflict and is a stark indicator of the trauma people in northern Mozambique are living through.

Cabo Delgado – On the Road to Stability?

By Piers Pigou, Cabo Ligado

What do the last months of 2022 tell us about the trajectory of insurgency and counterinsurgency in Cabo Delgado? Even for those following developments closely, like the Ligado team, access to data and corroborating violent incidents present an ongoing challenge, in the face of often official silence. As such, the picture oftentimes remains opaque, even contradictory; the introduction of foreign support troops 18 months ago certainly shifted the trajectory of the conflict, but only the most optimistic would predict an imminent or near-time victory.

The Mozambican government maintains an upbeat narrative, continuing to claim the insurgents are on the back foot, pointing to progress in the overall number of displaced that have reportedly returned to their home areas, or to district capitals that provide a staging post for many looking to return. Data released in January by IOM supports this, indicating that over 300,000 have returned.

This ‘normalization’ narrative is understandably contrived as part of the government’s efforts to promote a picture of control that will prompt the resuscitation of the liquefied natural gas (LNG) project that remains under a force majeure instituted in April 2021. TotalEnergies has been active in efforts to rebuild and resuscitate the coastal towns and related infrastructure of Palma and Mocímboa da Praia. TotalEnergies CEO Patrick Pouyanné stated in early 2022 that they would not restart the project until the security situation had improved sufficiently across the province. But what does that mean, and how realistic is it to think that sustainable pacification across the province is in the offing?

Many local and international analysts that Cabo Ligado has spoken to believe we are far from the end of this conflict and its associated humanitarian crises. Despite improved security in some key locations, large areas of Nangade, Muidumbe, and Macomia districts remain ungovernable. They provide space for ongoing attacks in these districts, but also for launching attacks into parts of Palma and Mocímboa da Praia districts, which have in the main, seen a major improvement in security. After successfully dislocating insurgents from their main bases in 2021, the security forces have struggled to hunt down and proactively engage the remaining fighters, many of whom effectively adapted to their new situation, extending operations, especially in the second half of 2022 into southern districts, as well as into Nampula on occasion. Two offensives into southern districts were tracked between June and November; these involved relatively small numbers of insurgents; they were able to generate widespread panic and a groundswell of newly displaced people. This illustrated a hitherto untested insurgent capacity to operate in southern districts.

Attacks in the southern districts tapered off from mid-November, with fighters believed to have rejoined other groups further north, ahead of the oath of allegiance sworn to the new IS caliph in early December. But these attacks, along with continued instability in Nangade, as well as north and south of the Messalo River basin (in Muidumbe and Macomia), have ensured security concerns have not dissipated, despite the official narrative.

In late November, Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame announced the expansion of the Rwandan mission in Cabo Delgado by an estimated 500 personnel; at the same time, Rwanda deployed up to 1,000 Rwandan troops and police officers from the north of the province to Ancuabe district as an official extension of their Areas of Responsibility. This appears to have been at the behest of President Nyusi and is intended to significantly bolster security options in southern districts and strengthen security on the southern section of the N380 road leading to Macomia. Within days, the EU had also confirmed it would be providing 20 million euros to support the Rwandan deployment through the European Peace Facility, following a request made by Kigali in December 2021.

Sources claim hundreds of additional Mozambican forces have also deployed in the south, as part of efforts to encourage the recently displaced from these areas to return as quickly as possible, to alleviate the burden on existing humanitarian infrastructure. The security context is complicated further by the re-emergence of a localized vigilante force known as Naparama last seen in the 1980s. They are particularly popular amongst the youth and actively confront insurgents. Naparama are seeking greater relevance in community security arrangements, especially given the government’s amendment of legislation governing Local Forces. The government’s reliance on auxiliary local militias illustrates their capacity limitations and highlights yet another aspect of the longer-term challenges to building stability and policing options in the province.

Counterinsurgency experts spoken to by Cabo Ligado have pointed out that the success of such operations is not a numbers game, in terms of throwing more personnel into the arena. While this may help contain the problem, it does not provide a long-term solution. There are now understood to be 4,500 foreign military and police in Cabo Delgado; SAMIM forces are now estimated at nearly 2,000, with over half of those deployed from the South African National Defence Force. The existing forces, they believe, are not fit for purpose, both in terms of numbers and the paucity of supporting (especially air) assets. As such, the capacity to hunt down insurgent groups is restricted. With the rainy season having begun, this capacity will be further restricted in the coming weeks and months. Current and recent security operations are likely to set the tone for 2023; recognition of the persistent threat of an insurgent presence in Nangade, Muidumbe, and Macomia has prompted various efforts to dislodge them over the last year. Insurgents who had decamped from southern Mocímboa da Praia in the face of the initial Rwandan offensive relocated to the Catupa forest, but were eventually forced to decamp from there in July 2022, relocating further west into Macomia and southern Muidumbe.

In late November, SAMIM launched a major operation around Nkonga in Nangade district, claiming it killed 30 insurgents in its most successful operation to date. But attacks in Nangade persist, albeit on a lower frequency. After a series of attacks on communities proximate to the high ground north and south of the Messalo river, the government launched Operation Vulcão IV, involving SAMIM and Rwandan forces, who have recently returned to Chai in northern Macomia. The success of this operation may have major consequences for insurgent fighting capacity, at least in the short to medium term. It will not, however, deal with the longer-term human security challenges, and the growing concerns and challenges associated with an increasingly radicalized insurgency.

Palma Is Back, Mocímboa da Praia Next

By Fernando Lima, Cabo Ligado

While you can feel tension in the air in Palma these days, the streets are colorful with people busy in their commercial activities, with dozens of small trucks and motorbikes on the streets. This is the new Palma, at the Afungi peninsula, the place where an attack by Islamist-inspired insurgents in March 2021 threatened Mozambique’s potential as a major exporter of LNG. TotalEnergies declared force majeure in its activities, and Mozambique was forced to call for foreign troops to contain an upsurge of violence that engulfed most of the northern part of Cabo Delgado province.

The heavy arm of the French major may be dormant, but small steps are being taken to have peace restored and a certain sense of normality reestablished. Thousands of Palma residents started to return last August under the protective shield of the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF). According to sources in Palma, people were given a “survival kit,” a food allowance, building materials, agriculture tools, and seeds. Merchants were given an “initial installment” of merchandise to sell, including zinc sheets, cement, and other emergency materials to rebuild their charred stores.

The government brought back its officials, including police, to have their part done in restoring normality at the district capital. Most of those who fled to Quitunda have returned. The town, 24 km further south, provided a ‘safe haven’ due to the 800-strong contingent from the Mozambican army, the so-called Joint Task Force assigned to protect the LNG site.

Shops are open; there is a new brick road connecting the upper town with the fish market and the beachfront. Even the Amarula Lodge is back, besieged by insurgents in March 2021. Two banks robbed by Mozambican troops after the March 2021 attack are ready to restart their activities to diminish the pressure on the only credit agency operating in the area, at Quitunda. A gasoline post is now functioning to the annoyance of those who did the shady deals with fuel siphoned from vehicles in the military barracks.

Rwandan police patrols are everywhere. They move on foot, or in 10-men units driven in single-cabin black Land Cruisers without license plates. The men are in full military gear, protection helmets, bulletproof vests, AK47, RPG7, a PK heavy machine gun on the top of the vehicle, and dark glasses. Despite the intimidating look, Rwandans enjoy notably friendly relations with local people. Children wave at their passage, and they speak Swahili with people. Their command posts often receive complaints on abuses against civilians, including offenses by Mozambican security forces.

Now, the operation for Palma is being mirrored for Mocímboa da Praia and smaller urban centers such as Pundanhar in the west of Palma district and Olumbe in the south. The road to Pundanhar, a 50 km stretch, is being repaired. Eventually, the onward 60 km stretch to Nangade district headquarters will be improved. The idea is to return the displaced people from the area still living in Palma town to their farmland in the west, and have a Rwandan garrison there.

A better road improves the security perimeter and offers an alternative commercial route via Mueda to the still problematic N380/N762 road further south. The road to Olumbe along the coast is a shortcut to the N762 and is located within the security buffer zone. It gives access to the sea for fishing communities, including populous villages such as Mondlane, Quelimane, and Maganja. It also improves communications with the small islands under the surveillance of the security forces patrolling the coastal waters. Arising from the road, a cold storage network helps the fishermen’s association, and their catches have a good market.

Along with Palma, Quitunda – a village constructed for people displaced by the LNG project – is being emptied of the displaced who fled there from the March 2021 attack on Palma. According to local sources, water and electricity have been restored to the 500 families living there. Radar Scape, a Rwandan company, is rebuilding 76 houses damaged while occupied by those displaced by the Palma attack. The housing complex could grow to 700 houses to accommodate the families of the community in Quitupo, the only urban settlement still within the boundaries of the LNG project. Under pressure to hire locally, a government institute promotes short-term vocational courses. Most of the trainees are now working in Quitunda.

Mocímboada Praia was the insurgents’ ‘capital’ for more than a year, but was retaken in August 2021 by the RDF, along with the Mozambican military. With a port and a 2,500 meters airstrip, it is a strategic logistic hub to neighboring districts of Muidumbe and Mueda, but it is also the urban center where the Islamist network that birthed the insurgency has its roots.

According to figures released by the provincial government and humanitarian agencies, over 70,000 people have returned to the area comprising all villages abandoned at the peak of the terror campaign waged by the insurgency led by the group calling themselves Ansar al-Sunnah pledging allegiance to the IS.

Security screening is very tight. Among security forces on the ground, there is the feeling the insurgency could be back in the town as a ‘Trojan horse’ formed by the waves of displaced. They come from several places: Quitunda, Palma, Montepuez, Mueda, and the emergency settlements in the vicinity of Pemba, the capital city of Cabo Delgado, now with a population of 400,000 people.

At the airport, the runway still needs major repairs and navigational equipment to receive large planes, which are currently landing at Afungi. But the port is now functional. Barges coming from Pemba bring all sorts of materials to rebuild the town, including vehicles and accessories to remove the garbage. Government bureaucrats live in tents while the destroyed buildings are being fixed. The bill is being paid discreetly by TotalEnergies, while the groundwork is being done by the MASC Foundation, a multidisciplinary Mozambican organization led by Professor João Pereira, Cabo LIgado has learned.

After the push on insurgency bases along the Messalo river, small rebel groups have been active since October, attacking vehicles on the N762 road and the repopulated settlements. Security analysts note the eventuality that the Rwandan force is too overstretched after an initial commitment concentrated on Palma and Mocímboa da Praia.

With the shortcomings of the Mozambican forces and the underperformance of the SADC contingent, the RDF was called to operate in Nangade, Macomia, and Muidumbe. Their initial force of 1,000 was increased to 2,500 in late November last year. After insurgent units launched an offensive in August, attacking districts in the south of Cabo Delgado and making a deadly incursion in Nampula, across the Lurio river, RDF agreed to establish a garrison at Ancuabe, a strategic position trying to protect the graphite and ruby mining industry affected by the attacks in the south.

Despite the positive developments, neither Palma nor Mocímboa da Praia is wholly secure. And military escorts are back on all roads leading to Mocímboa da Praia. After a recent road ambush in the boundaries of the town, a local reporter quoted an insurgent shouting to a frightened minibus driver: “who told you we were out of Mocímboa?”

Can TotalEnergies be on in 2023?