Cabo Ligado Monthly: June 2020

June at a Glance

Vital Stats

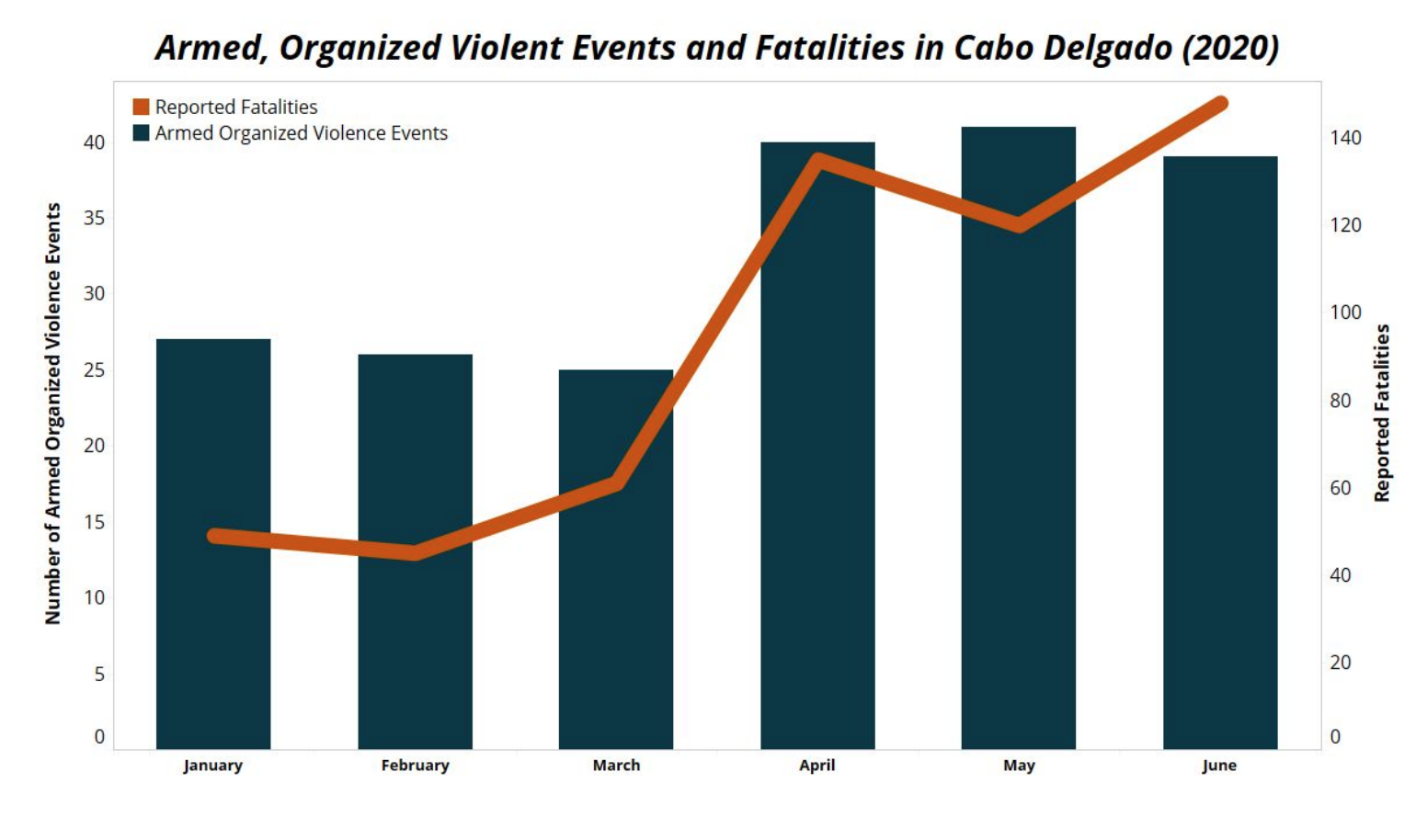

ACLED records 38 conflict events in June 2020, resulting in 80 reported fatalities

That represents a decrease in conflict events, but an increase in fatalities, from May 2020

Conflict events took place in Macomia, Meluco, Mocimboa da Praia, Muidumbe, Palma, and Quissanga district, but the vast majority happened in either Macomia or Mocimboa da Praia

Vital Trends

The ratio of insurgent attacks on high value targets to small-scale insurgent attacks increased in June

State security forces demonstrated a new level of willingness to commit violence against civilians as part of counterinsurgency operations in Mocimboa da Praia

Civilian displacement is still rising, particularly as a result of the battle for Mocimboa da Praia

In This Report

An in-depth analysis of the situation in Mocimboa da Praia

Updates on regional efforts to provide material assistance for Mozambique’s counterinsurgency effort

An evaluation of government security force June offensives

June Situation Summary

Cabo Delgado remained volatile in June, with insurgents executing fewer, higher value attacks than in May, causing massive infrastructure damage. Those attacks, particularly at Mocimboa da Praia, dominated headlines, although smaller-scale attacks also took place in Meluco, Muidumbe, Palma, Macomia, and Quissanga districts. Among the results of the month’s attacks was a continued deterioration of the humanitarian situation in Cabo Delgado, with many more civilians displaced from Mocimboa da Praia district and aid still not getting through to too many people in need.

At Mocimboa da Praia on 26 June, insurgents demonstrated their increasing sophistication by planning and executing a complex operation and directly targeting Mozambican troops. Though insurgents withdrew from the district capital once they demonstrated their ability to hit the town at will, the attack -- combined with government missteps before and after -- drove civilians from Mocimboa da Praia in droves, leaving it a ghost town.

The frequency of smaller-scale attacks, which serve to create corridors of control for the insurgency, allow fighters access to main roads, and coerce civilian support, vary widely week to week but are likely to continue for the foreseeable future. No evidence emerged in June of insurgents trying to create new governance structures in areas they control. Instead, they remain focused on exerting control for short periods of time, continuously conveying a message of undeterred presence and capacity, countering the government’s narrative that it is making progress against them.

The government’s record in June was murky at best. The extent of the government’s success attacking an insurgent base at Marere, Mocimboa da Praia district, on 9 June, remains shrouded in mystery due to the lack of evidence the government has provided of the alleged 100 insurgents that were killed. On 13 June, the Mozambican military, supported by the helicopter gunships from Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) attacked insurgents in Chinda, Mocimboa Da Praia district, but no fatalities were reported. Victor Novela, Director of Operations of the Mozambican Police General Command, claimed successes at Rua-rua, Rio and Ngure, Muidumbe district, but, again, evidence of actual insurgents killed was not provided.

What is not in doubt, though, is an alarming level of abuse of civilians in Mocimboa da Praia town. In the days before the attack on Mocimboa da Praia, civilians complained of disappearances, beatings, and extra-judicial killings by soldiers engaged in counterterrorism operations. After insurgents were driven out, lawlessness reigned in the district capital, which resulted in widespread destruction and looting, including by security forces, which drove whatever civilians were still left from the area. Overall, the level of trust by the population in government forces’ ability to deal with the armed incursions remains low.

The Mocimboa da Praia Attack

The 26 June insurgent attack on Mocimboa da Praia showed insurgents’ intent to focus attacks on high value targets. The pace of attacks across the province slowed in the days leading up to the Mocimboa da Praia raid, and insurgents clearly used the time to plan a sophisticated operation.

Insurgents reportedly attempted to arrive in Mocimboa da Praia both by dhow and over land, coordinating between three attacking groups. Insurgents suffered losses during the first round of attack, retreated, regrouped, and then proceeded to gain control over part of the town. This level of grit could be attributed to foreign influence, as local insurgents lack battlefield experience to adjust, regroup and attack. Insurgents remained reliant on direct contact weapons, though Islamic State photos reveal an ever-expanding range of indirect fire weapons in insurgent caches.

High value target attacks becoming a greater proportion of insurgent operations represents an increased risk for Cabo Delgado’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) sector and sub-contractors associated with those projects, humanitarian organizations and aid workers, centers for displaced people, as well as state security forces. So far, the LNG sector’s approach has been to try creating high levels of security in pockets around project sites. However, securing the LNG sites is a far cry from enabling a secure environment for contract workers and expats commuting beyond the site. LNG sites simply cannot isolate themselves from the rest of Cabo Delgado. That said, there has been no outward shift in LNG sector security posture. On 4 July, Total announced that it will continue to rely on the government for its security needs, as it has until now.

The Mocimboa da Praia attack was partially a response to government security force operations days prior to the attack. Following reports on security force abuses, insurgents most likely realized the opportunity to gain support from locals by directly confronting government soldiers. At the start of the attack, insurgents reportedly informed civilians that they were not the primary target of the attack, part of insurgent efforts to drive a wedge between civilians and state forces. Those efforts, bolstered by government security forces’ tendency to rely on coercion when dealing with civilians, help insurgents both operationally and in recruiting.

As the Mozambican government’s hard power approach leaves more youths frustrated, it will likely provide an ideal recruitment opportunity for insurgents. MediaFax quotes sources saying that most of the youth supporting the insurgency do so as a response to security force human rights abuses and not out of ideological conviction, although that conclusion is contested among analysts. Current government tactics merely reinforce discontent and provide insurgents with a ready-made justification for their use of violence.

Government interventions will to a great extent determine how the insurgency is viewed by local civilians. As Islamic State propaganda about Cabo Delgado becomes more detailed and specific, we should be cautious not to lose sight of local drivers of discontent as sources of conflict. It is not a question of choosing between local or international factors to explain the conflict, but of understanding how local audiences understand both when making decisions about how to respond to ongoing fighting.

Regional Developments

Unsurprisingly, details of possible Southern African Development Community (SADC) assistance to counter the insurgency in Mozambique remained scant through June. Bilateral negotiations continued between Mozambique and the regional bodies’ member states, feeding into the work of the Inter-State Defence and Security and Interstate Politics and Diplomacy Committees that had been tasked to explore options by the Organ for Politics Defence and Security. SADC has various strategies (anti piracy, counter terrorism) to work with, and recently reviewed its maritime strategy, but these options must be adapted to the specific challenges faced in Cabo Delgado. A virtual meeting of these committees on 25-26 June resulted in some progress, including, according to some sources, commitments from some countries for boots on the ground, but an overall strategy has not been locked down. The process of doing so is frustrated by the reluctance of some actors, Mozambique’s need to remain “in charge” of the situation, and practical realities, such as who will pay.

The Troika’s May communique called on member states to support Mozambique’s efforts; this can take on a variety of forms, from actual deployment, to sharing of intelligence, the provision of supplies, equipment and training. The communique does not specify that support must take the form of armed intervention, although it is clear Mozambique could benefit from direct assistance. Any such intervention would require the go-ahead of SADC member states; at the current pace, it is possible that this might even occur at the scheduled SADC Summit in early September, where Mozambique will take over the chair from Tanzania. The SADC imprimatur is likely to be a formal window dressing for a set of bilateral agreements; what role the regional body plays in oversight and review remains to be seen, but Mozambique’s insurgency is likely to be a formal file for the foreseeable future. This is unchartered territory for SADC, which must balance evident regional security interests with sovereignty politics from Mozambique, which will want to maintain as much control over what assistance is provided and how as possible.

Although South Africa remains the most likely country to provide support, and has been assessing its options in this regard, there is no evidence that it has made any specific additional commitments in Mozambique. Repeated defense budget cuts over the last decade have gravely eroded capacities, and the recommendations of the 2015 Defence Review continue to gather dust. Over $600 million has been cut from the department’s budget in the last three years and a further $300 million will be cut in 2021.

South Africa already has a maritime security agreement with Maputo – Operation Copper – designed to tackle piracy in the Mozambique channel; this agreement currently involves 200 South African personnel, was extended for another year in April, and could be reconfigured to accommodate a Special Forces maritime capacity. This would be a helpful fillip in efforts to ramp up the maritime component of the wider counter insurgency operation. Insurgents have on several occasions launched attacks from the sea on coastal villages as well as off-shore islands; they are also believed to rely on coastal transportation and supply lines. Policing this is significantly complicated by the increasing numbers of IDPs using coastal routes in search of sanctuary.

The region, and South Africa in particular, remain silent about the Dyck Advisory Group’s (DAG) involvement in Cabo Delgado. This suggests that agreement may have been reached on some sort of legal exemption for DAG; clearly for South Africa this is a particularly sensitive issue, especially given DAG’s blatant offensive role in the fighting. DAG’s role should not be underestimated; it has been pivotal in Mozambican security forces’ efforts against insurgents over the last three months, but its aerial attacks and surveillance role can only achieve so much in the absence of an effective ground attack force capacity. This also necessitates enhanced troop deployment capacity by land and air; this hardware is currently not available. DAG’s contract has reportedly been extended until at least the end of the year and will now include a ground force training component. DAG’s aerial support has been a central pillar of the Mozambican counterinsurgency effort since April; if they are to be drawn down from this role, which seems unlikely, a replacement force, ideally with augmented capacity, must replace it. Whether this is feasible remains to be seen. It is unclear how Mozambique is paying for the DAG contract, and what SADC member states are willing to allocate in a context of their competing spending priorities.

Observers are watching the reaction of other neighboring countries keenly; Tanzanian cooperation is of particular importance given its shared border with Cabo Delgado and its own longer-term plans to develop its off-shore liquid natural gas resources. The Mtwara region is particularly vulnerable given its proximity to Cabo Delgado. Tanzanian nationals are accused of playing an important role in the evolution of the insurgency, from catalyzing radicalization to provision of supplies and direct participation in attacks. Some insurgent attacks have been geographically proximate; in June 2019, eleven civilians were killed by gunmen near the border with Tanzania; media reports claimed Mozambican security force action prevented the attackers crossing into Tanzania. In November, six villagers were killed and another seven injured in a border village on the Ruvuma river during an insurgent attacks.

Dozens of Tanzanians have reportedly been prosecuted, and many convicted, by Mozambican courts for their role in the insurgency. In October 2018, Tanzanian police chief, Simon Sirro, claimed armed Tanzanians were seeking to establish a base in Mozambique and that the group, “including young girls, were … responsible for several murders of police officers and administrative officials in Tanzania's eastern Pwani province in 2016 and 2017.” In 2016, the coastal region of Pwani (north of Mtwara) was hit by a series of suspected terrorist attacks resulting in the killing more than thirty police and low-level ruling party officials. A subsequent crackdown by Tanzanian security forces led to the alleged disappearance of almost 400 people in 2016 and 2017. Sirro claimed Tanzanian police had arrested 104 members of this group trying to cross over the border into Mozambique.

Following the November 2019 attack, Mozambique’s then defense minister, Salvador M’tumuke, and his Tanzanian counterpart confirmed “the need for regular meetings to exchange information pertinent to the security of both countries.” Those meetings were subsequently put in place.

In June 2020, Mozambique’s defense minister, Jaime Neto, claimed two insurgent leaders from Tanzania had been killed during the battle for Macomia; social media reports claimed the two men were on Tanzania’s most wanted list, but Tanzania has neither confirmed, nor denied this.

Tanzania’s ambassador in Maputo, Rajabu Lahawi, subsequently countered claims that Tanzania was not invested in countering the insurgency, pointing to the expanded security force deployment along the border area and implementation of joint patrols. In March, additional troops were sent to Msimbati and Sindano areas of the Mtwara region. Both countries have weak security and intelligence capacity and the border is notoriously porous, infamous as a major transit route for heroin smuggling. In addition, Tanzania has its own militant Islamist issues and will be keen to avoid publicly baiting the bear. On 1 July, Mozambican president Filipe Nyusi’s office confirmed he had spoken with his counterpart in Tanzania, John Magufuli, covering a range of issues including defense and security concerns and had “agreed to strengthen their coordination in the fight against this common enemy”, suggesting that previous efforts to do so may well have been insufficient.

The Dubious Record of Government Offensives

June saw the most complete expression of the Mozambican government’s new approach to counterinsurgency. Using its increased deployments of ground troops and the air assets provided by DAG, the military has moved from an earlier tactic of garrisoning villages and waiting for insurgents to come to undertaking large-scale offensives aimed at actively rooting out insurgents from villages and remote bases alike. Though the earlier garrisoning approach was clearly a failure, the results of the new offensives are mixed at best. There seem to have been some real victories when government troops confronted insurgents in the bush, but when offensives reach towns and villages, the results have been growing allegations of human rights abuses by the military and a quick return to insurgent attacks in areas the government claims to have liberated.

The first iteration of this trend happened in Quissanga district in May, after a late April insurgent attack on Metuge district provoked a major government counterattack that ended up pushing north through Quissanga. That initial offensive provided the blueprint for future government offensives: DAG-led attacks claiming to have killed dozens of insurgents and destroyed insurgent bases, gradual insurgent retreats in the face of government advances, and calls from local authorities for civilians to return to their homes. While there have been security improvements in Quissanga -- the area of insurgent influence closest to the government’s military and logistics hub in Pemba -- it became clear in June that not all insurgents withdrew in the face of the government’s advance. Instead, some stayed behind, and have continued attacks with relative impunity. In June, ACLED registered five attacks on civilians in Quissanga district, resulting in four deaths and the destruction of many homes.

June also saw the start of two new government offensives, first in Macomia district and then in Mocimboa da Praia district. The timing of the Macomia offensive was dictated by the insurgency -- the government was forced to respond after insurgents occupied Macomia town on 28 May. Efforts to push insurgents out of the district capital and surrounding villages such as Chai, Litamanda, and Nova Zambezia took several days and resulted in multiple civilian casualties. The government claimed to have killed 78 insurgents, including two insurgent leaders, during that time, although no evidence for those claims has been brought forward. Yet, even if those death counts are inflated, this may be the most successful of the three offensives from an ongoing security perspective. Since the government retook Macomia and its surrounding area, ACLED registered only one June attack on civilians in the district’s inland Macomia and Chai administrative posts, which are where the counterattack took place. That attack, which took place on or around 14 June, resulted in the beheading of four motorbike passengers who were on the road -- away from where government troops were deployed.

State security forces’ focus in June, however, was on Mocimboa da Praia district. On 9 June, the government launched an attack on an insurgent base in Marere, on the district’s southern border with Macomia district. The attack pushed insurgents out of a stronghold and forced them to break up and withdraw north. Government troops advanced in their wake, pushing on and harassing retreating insurgents at Makulo, Cabacera, and Chinda. It looked as though the government had insurgents on the run, and troops in Palma prepared themselves for a northward wave of insurgents leaving Mocimboa da Praia district.

Instead, insurgents slipped back behind government lines and, on 27 June, retook Mocimboa da Praia town, forcing the government into a running battle to once again secure the town. The insurgents’ ability to reform into a cohesive fighting force, apparently at will, after a fractured retreat is both an indication of their command and control capabilities and of the inadequacy of the government’s kinetic operations to quell the insurgency.

What makes the Mocimboa da Praia attack a particularly strong indictment of the government approach was the intense ratissage that preceded it. Soldiers and police went door to door in many Mocimboa da Praia neighborhoods, beating many and killing some in an effort to root out insurgents and collaborators. 26 bodies, dumped just outside town, are believed by locals to be civilians who the government summarily executed under suspicion of being associated with the insurgency. To commit atrocities at that scale -- as yet unprecedented from the government in this conflict -- demonstrates how deeply the government believes that increased violence can end the insurgency. To have those atrocities backfire as spectacularly as they did on 27 June demonstrates the danger of violent escalation as the government’s main response to insurgent provocation.

In the long run, it may be some time before we know how much of the drop in attacks in the wake of government offensives in certain areas is due to insurgent retreat and how much is due to civilians vacating those areas, giving insurgents fewer targets. Already, though, we know that these offensives themselves will not finish this fight. Even with security forces terrorizing civilian populations, insurgents survive in areas the government claims to have released from their grasp.