Cabo Ligado Monthly: November 2021

November At A Glance

Vital Stats

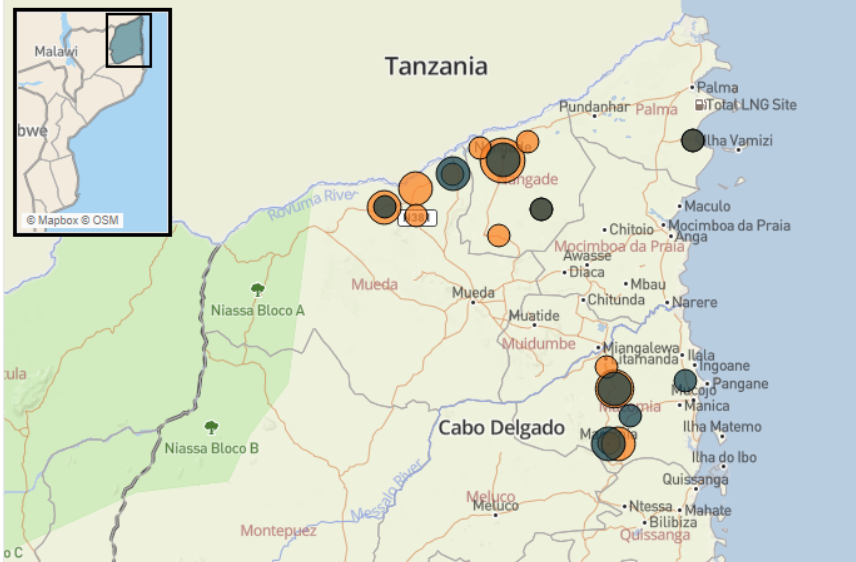

ACLED records 37 organized political violence events in November in Cabo Delgado province and three such events in Niassa province, resulting in a total of 92 reported fatalities

Reported fatalities were highest in Macomia district, where insurgents repeatedly carried out attacks on civilians and clashed with Mozambican state forces, local militias, and troops from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Standby Force Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM)

Other events took place in Chiure, Mueda, Nangade, and Palma districts in Cabo Delgado, as well as Mecula district in Niassa province

Vital Trends

The conflict expanded westward in November, with insurgents pushing into Niassa province at the end of the month

That westward expansion, in combination with the heavy fighting in Macomia district, highlights the fact that the insurgency still retains significant capacity for violence and that the combat phase of the conflict is far from over

Only two events were recorded in Palma district, indicating the continuing growth of the eastern part of that district as an enclave, separated from the rest of the province to pursue liquified natural gas development

In This Report

Analysis of the politics surrounding natural gas projects in both Tanzania and Mozambique in light of the current conflict situation

Discussion of the role suspicion plays in shaping interactions between displaced civilians and Mozambican security forces

Examination of recent shifts in the roles of Rwandan and SAMIM forces in the conflict

An update on SADC’s thinking about the future of SAMIM

November Situation Summary

The story of November in the conflict in northern Mozambique is the reconstitution and expansion of the insurgency’s fighting power. After a low ebb following battlefield successes by Mozambican forces and foreign intervenors, in November, insurgents began once again to fiercely contest control of northern Macomia district and to expand the conflict zone west into Niassa province, a part of the country that had not yet experienced violence from the conflict.

The shift west began with increased insurgent activity in Nangade district, then a spate of attacks in northern Mueda district, and finally, at the end of the month, resulted in three organized political violence incidents in Niassa province’s Mecula district. By and large, these attacks were at least partially directed at resource gathering, as the insurgency seeks to recover the logistical structure it lost when its Mocimboa da Praia district bases were overrun in August and September of this year. In Niassa, they were met at first with denial from local officials, and with widespread fear from civilians in the area of the attacks.

That fear, along with some house burnings by insurgents, have led to new fronts of displacement in the conflict. In Mueda district, Cabo Delgado province, attacks in the north drove well over 3,000 people to leave their homes just between 10 and16 November. Statistics for Mecula district in Niassa province are harder to come by, but at least 600 people had fled their homes by early December, and the Mozambican government had begun organizing humanitarian support for displaced people in Niassa. It is unclear how far the violence in Niassa will extend, but there is potential for a significant expansion of Mozambique’s already dire displacement crisis.

The insurgency’s return to the offensive also coincided with the return of the Islamic State (IS) into the international discourse around the conflict. IS issued over 20 claims of insurgent attacks in November, many of them confirmable with independent sources and often within days of the attack taking place. The return to frequent claims, which has extended into December, indicates that the communications link between IS and the insurgency is fully functional and that IS still sees Mozambique as a worthwhile franchise. IS has been particularly dogged about publicizing the insurgency’s push westward, as if it is working to cover for the insurgency’s losses in Mocimboa da Praia and Palma by hyping up its gains in Mueda and Mecula.

The situation in eastern Palma district, however, appears to be returning to a level of normality that was nearly unimaginable six months ago. With regular overland travel between Palma town and Mueda and security protocols in place, enforced by Rwandan troops, Palma appears to be once again open for business. The Mozambican government’s intention appears to be to set it aside as an enclave that can host natural gas projects and serve as an economic engine for the country. At the moment, its enclave status seems well in hand, but the reliance on Rwandan troops to enforce it leaves Mozambique very much at the mercy of the Rwandan government’s willingness to extend its deployment in Mozambique. With so much unknown about the arrangements between the two countries, it remains to be seen how long this period of relative prosperity will last in Palma.

The Future of LNG on Both Sides of the Ruvuma

The commercialization of natural gas reserves in Mozambique and Tanzania will remain central to public safety, national security, and political power in both countries in coming years. In November, Tanzania started a new round of talks with Equinor and Shell to agree a framework for the mooted liquefied natural gas (LNG) project in Lindi Region. Also in November, a floating LNG facility started its voyage from South Korea to Mozambique’s offshore Area 4. Total’s Senior Vice-President Africa Henry-Max Ndong Nzues expressed guarded satisfaction with operations against the insurgents in Cabo Delgado, though stopped short of resuming project development. On 25 November, Mozambique launched its Sixth Licensing Round, with five of 16 offshore blocks being off Cabo Delgado province. All these projects have varying timelines but will inevitably affect the security situation on both sides of the border for years to come.

On 8 November, talks concerning a host government agreement for Tanzania’s LNG project officially re-commenced with energy companies. Though the aim of completing the talks by May 2022 is unlikely to be met and a final investment decision is likely a long way off -- and may never come -- heightened activity can be expected in Lindi town, the future site of the LNG plant, and Mtwara town, a base for any future offshore developments of the southerly Shell operated fields. Much of this will be positive, particularly for Tanzanian private sector investment. Yet, recent history has some lessons for how such activity may be received locally, and its potential impact on political violence.

In January and May 2013, in Mtwara, Tanzania experienced its greatest outbreak of civil unrest since the Majimaji rebellion over 100 years before. In December 2012 and January 2013, mass demonstrations were held to protest a proposed natural gas pipeline, under the slogan “Gesi Haitoki Mtwara” (the gas is not leaving Mtwara). The demonstrations were led by some Mtwara NGOs, local branches of opposition political parties, and religious leaders both Christian and Muslim. The demonstrations were followed by seemingly organized violence across Mtwara Region.

Clashes in January saw politicians’ homes, a prison, government and ruling party offices, and government vehicles attacked. Mtwara town, Tandahimba, and Masasi were all affected. Clashes occurred again in May after the presentation in parliament of the budget for the Ministry of Energy and Minerals. This led to the deployment of troops in Mtwara town.

Current state concerns about security in the region stem from the violence of that period. The government believed that the 2013 violence was instigated for political reasons, and reacted accordingly. The then-member of parliament for Mtwara Urban was charged with incitement, while a Tanzania People’s Defence Force commander pointed the finger at religious leaders, motorcycle taxi drivers, and city businessmen, accusing them of organizing the violence. Less publicly, informants in Mtwara town have spoken of Salafist elements having had a hand in the violence.

The lesson for 2021 and beyond is that the use of violence in response to LNG development is not restricted to extremists. Shell’s natural gas reserves lie close to Mtwara town. Shell and its subcontractors will need to expand their presence in order to develop the reserves, which requires significant infrastructure development. The impact in Lindi will of course be greater if the LNG plant goes ahead. Project benefits will need to be cannily distributed, and rents will need to be managed in politically sensitive ways.

The security risks in Cabo Delgado are of course more acute. Total suspended operations on its Mozambique LNG project in April 2021 following the attack in March on Palma town by the insurgents, a decision that has contributed to further delays to the ExxonMobil-led Rovuma LNG project. This followed the withdrawal of staff from the project in the face of an insurgent attack in January on Quitunda, which is beside the project site. The attack highlighted France’s strategic interests in at least containing the insurgency to allow the project to go ahead. Rwanda’s success in securing the enclave of Palma town and the neighboring LNG site, while fighting continues across Cabo Delgado and Niassa provinces, confirms for some Rwanda’s role as a proxy for French interests.

The January and March attacks on Quitunda and Palma saw IS propagandists cite France as exploiting Muslim communities, in one case comparing Mozambican gas to West African gold. If Rwandan and Mozambican forces are successful in securing Palma and the Afungi peninsula as an enclave, and resume Mozambique LNG, France may find itself increasingly tied to the project’s security risks. Given Total’s interests in Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Tanzania, France will undoubtedly continue to exert its influence on security matters across the region.

In the longer term, Mozambique’s 6th Licensing Round too has the potential to drive extremist narratives for years to come, if successful. The round, launched in November, will close in October 2022. Three offshore blocks lie off Chiure, Pemba, Quissanga, Ibo, and Macomia districts. Their development will depend on the province’s long term security, or failing that, the development of an expanded coastal enclave. The model that Mozambique pursues to manage the security risks around LNG development -- and the success of that model -- will have major economic and governance implications on both sides of the Ruvuma. If Mozambique LNG development cannot survive the political upheaval that has grown in its wake, Tanzania is likely to take a much more repressive approach to its own LNG projects.

Managing Suspicion of Civilians

Throughout the conflict in Cabo Delgado, various reports from media organizations, research institutions, and humanitarian organizations have raised evidence of a number of people who have been detained by Mozambican security forces on suspicion of collaborating with insurgents in Cabo Delgado. A report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) published in December 2018 accused Mozambique's security forces of detaining, mistreating, and summarily executing individuals suspected of belonging to the insurgency. Amnesty International , in a report published in October 2020, accused the Mozambican army of carrying out executions and detaining journalists, researchers, and community leaders on suspicion that they were collaborating with insurgents.

Incidents illustrating the situations described by human rights organizations continue to take place in the conflict-affected areas of Cabo Delgado. In November, local militia were reported to have killed two suspected insurgents in Macomia. Outside Cabo Delgado, in early November the southern province of Inhambane, police detained and later released 15 individuals from Cabo Delgado who were working for a Chinese fishing company off the coast of Inhambane after suspecting them of being members of the Cabo Delgado insurgency. On 19 October, local forces detained three civilians who were later handed over to the Mozambican police, accused of spying for the insurgents in Nangade. On 7 April, pro-government militias executed four individuals suspected of being members of the insurgency. Earlier in the year, police shot dead a suspected insurgent informant in the resettlement village of the Afungi LNG project in Cabo Delgado.

In the resettlement zones, sources report that displaced people fleeing the conflict are also suspected of collaborating with the insurgents, and in some cases accused of wanting to bring the war to southern Cabo Delgado. These accusations are based on the fact that the displaced persons speak Kimwani, a language often associated with the insurgency, and come from the areas of conflict in the province. Allegations of government prejudice against displaced people are reinforced by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, which reports that displaced persons face discrimination and random interrogations and harassment by Mozambican security agents.

The pervasive sense of suspicion directed at civilians in the conflict zone dates back to the start of the conflict in 2017. Displaced people from Mocímboa da Praia who are now in Nampula say there is a belief that the individuals who organized the first attack on Mocímboa da Praia on 5 October 2017 were of Mwani ethnicity. After order was restored in the area, several people from other ethnic groups suggested the police should search homes belonging to Mwani citizens, which created some dissatisfaction among them. From then on, sources say, the Mwani population felt marginalized and unprotected by the security forces, and refused to cooperate with the authorities in identifying possible insurgents. The behavior of elements of Mozambican security forces, characterized by mistreatment and summary executions of civilians, further reduced trust and collaboration between the military and the population.

Meanwhile, in Nangade district and other areas with smaller Mwani populations, collaboration with government security forces is stronger. In Nangade, for example, the population tends to report movements of suspected insurgents to local authorities, local militia, and defense and security forces. When the absence of a person is noted, the population seeks or consults the local leader to see if the person has requested a travel document to another place. If not, this is cause for investigation until the individual is located. In situations where the person is not located, it is assumed that he or she has joined the insurgency.

At the same time, throughout the conflict, government authorities have introduced mechanisms to ensure the identification of those suspected of belonging to and/or collaborating with the insurgency. One such mechanism is the issuing of a 'guia de marcha,' a document issued by the village chief to all those who want to move from one place to another. The document is issued at a cost of 100 meticais ($1.55). Whenever they are stopped by local forces, police, or soldiers, civilians must present this document. The document contains the name and contact details of their village leader, who can confirm whether the person has authorization to leave their village or not. If someone is stopped and is not carrying a guia de marcha, they can be subject to extensive interrogation.

Of course, some civilians actually are supporting the insurgency. Family members of insurgents and other civilian supporters have assisted insurgent logistical flows by providing supplies and withdrawing sums of money through mobile finance systems. According to a source in Macomia, the collaboration also occurs when family members request travel documents for relatives who are in the insurgency, which will allow them to flee or move elsewhere. A study conducted by Mozambique’s Rural Environment Observatory, a Mozambican non-governmental organization, on the social organization of the insurgents, noted that women who have joined the insurgents voluntarily or by coercion often carry out observation and espionage activities.

The Mozambican government denies the accusations of abuses made against it by human rights organizations, saying its actions are in defense of the country and the Mozambican people. Yet the evidence that groups like HRW and Amnesty International bring to bear is overwhelming, and there is little evidence that the state’s campaign of violence against those it views with suspicion is deterring such collaboration as there actually is between civilians and insurgents. As the conflict’s geographic footprint expands, it will only become more important to curb the government’s tendency toward violent repression of populations it deems at risk of collaborating with the insurgency.

Shifting Responsibilities in Northern Mozambique

One notable shift in the conflict in northern Mozambique in November has been the breakdown in defined areas of responsibility for the foreign forces intervening on the Mozambican government’s behalf. At the beginning of SAMIM’s deployment in Cabo Delgado, the apparent division of labor between the SADC force and the Rwandan military was relatively clear. The two forces would divvy up the work of counterinsurgency not by mission but by area, with the RDF taking responsibility for Palma and Mocimboa da Praia districts while the smaller SAMIM force focused on the calmer districts of Macomia, Muidumbe, Mueda, Nangade, and Quissanga districts. That division held for months, even as Rwandan officers complained that insurgents they pushed south across the Messalo river were not being captured by their SAMIM counterparts in Macomia district.

In November, however, reports began to emerge that RDF units were appearing in locations within SAMIM’s area of responsibility. During the week of 22 November, RDF troops occupied the village of 5º Congresso in Macomia district, some 25 kilometers south of the Messalo. The move appeared to be a response to ongoing insurgent activity in the village -- insurgents had attacked the village twice in the previous two weeks. Speaking to sources on the ground, it quickly became clear that the Rwandan mission in 5º Congresso reflected a shift in perception -- and perhaps strategy -- among the intervening forces.

Increasingly, people living in the conflict zone view the work of the intervening forces as being divided not along geographic lines but among different roles. SAMIM, as one source put it, “are there to maintain stability, [and to] provide protection” to civilians in the areas where they are deployed. The RDF, conversely, are seen as the sharp end of the spear, the force that gets called in to conduct offensive operations when insurgents are operating on the front foot. Their use as offensive forces extends beyond their recent push into Macomia district. In addition to the 5º Congresso operation, Rwandan forces were also spotted in Mueda district near Ngapa following insurgent attacks there, and in Niassa province’s Mecula district following the beginning of insurgent operations there. Conversely, shifts in SAMIM forces have largely been non-combat focused. The Lesotho Defence Force announced recently that, in early November, its contingent of troops had moved temporarily from Nangade to Muidumbe district to destroy five deserted insurgent camps.

On one hand, there are some short-term positives to this new distribution of labor for the pro-government coalition’s counterinsurgency effort. The RDF, the largest single foreign force in northern Mozambique, has the resources to conduct offensive operations in multiple areas around the conflict zone. There have been no reports of blue-on-blue violence, suggesting effective coordination between RDF and SAMIM forces, and, at least in 5º Congresso, Rwandan intervention appears to be useful. There have been no further insurgent incursions into the village since the Rwandans arrived (although other insurgent operations in Macomia district are still ongoing).

Yet, in the long term, the shift in perceptions of SAMIM and the RDF could be damaging to the counterinsurgency effort. As the conflict rages on despite Mozambican government assurances that it is winding down, the need for offensive action beyond basic civilian protection is likely to expand. At the same time, SAMIM’s apparent inability to take on that role is already beginning to undermine local confidence in SADC forces. Local sources in Macomia district expressed frustration with ongoing violence there despite SAMIM deployment in the area, and residents of Mecula district have publicly declared that they see Rwandan intervention there as being their only hope of seeing order restored to the district. If RDF troops become the sine qua non of security provision in northern Mozambique, it will both stretch the resources of the Rwandan deployment and leave the security situation in the region hostage to the whims of the Rwandan government. That quickly turns into a vicious cycle, in which growing demands on the RDF increases resource pressure for Rwanda to draw down its deployment, generating further insecurity.

The core problem for security provision in Cabo Delgado is that there are few troops in the pro-government coalition and a huge amount of geographic area that they must protect as civilians return to their homes. A situation in which RDF troops are responsible for responding to insurgent attacks in an ever-expanding area is not sustainable in the long term. SAMIM and Mozambican forces will have to prove themselves capable of conducting effective offensive operations if the pro-government coalition is to durably alter the security situation in northern Mozambique.

SADC Update

As the SAMIM mission heads towards the end of its current mandated deployment in mid-January, the mission continues to make some operational gains, but still faces a series of unresolved questions about its long-term future.

On 8 November, SAMIM’s political head, Mpho Molomo, told a public webinar in Pretoria that SAMIM forces (alongside Rwandan and Mozambican forces) had been instrumental in stabilizing the security situation, which “has allowed the Mozambican Government, together with International Cooperating Partners, and multilateral agencies of the United Nations to roll out the much-needed services as well as humanitarian assistance.” Molomo pointed to improvements in communication and coordination with Rwandan and Mozambican forces following the establishment of a joint coordinating liaison committee comprised of generals from the three forces.

Operational progress includes the killing of insurgents, over 150 hostages rescued, and recovery of items such as medicine, foodstuffs, generators, computers, documents, and vehicles. Molomo indicated around 15,000 displaced persons had been able to return to their homes as a result of SAMIM’s efforts.

In the bigger picture, there is evidently much more to be done. According to one estimate, over 2,000 insurgents are unaccounted for, as are hundreds of hostages. Stability in many areas remains fragile, as evidenced by the limited numbers of displaced people returning home and the caution from humanitarian agencies in resuming operations. The mission in many ways remains in its formative stages.

Molomo acknowledged that military intervention is only one aspect of the challenge and that securing Cabo Delgado necessitated a return of law and order and the rule of law, alongside the restoration of public services such as electricity, water, and the reopening of schools.

On 10 November, SADC itself released an update on the SAMIM deployment, setting out basic facts about its mandate, and core areas of progress, but revealing little operational detail. On 11 November, SAMIM issued another media release, claiming it had destroyed three insurgent bases north of Lake Nguri and the Muera river in northern Macomia as part of a major operation launched on 24 October. The statement emphasised SADC’s commitment to helping Mozambique to create conditions for a return to normal life for the people of Cabo Delgado.

Measuring advances towards this goal presents a significant challenge. SAMIM’s Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) does not provide a framework against which SADC can assess progress to determine whether mandate objectives have been achieved, and, in turn, benchmarks and modalities for drawing down the mission remain undefined. A SADC meeting of Troika officials in Pretoria on 25 November sought to set out what such a framework might look like. Ahead of SADC’s formal Troika meeting in January, SAMIM will conduct its own internal assessment of the mission’s progress. The Troika is expected to extend the mission’s mandate for a further three months, but whether this will include an expansion of personnel and a commitment to moving beyond a hard security focus will be contingent on funding and political developments. In the meantime, additional South African forces have been approved, but remain on standby.

While SADC does not want to get drawn into an expensive, drawn out deployment, it believes an unstable Mozambique will undermine wider regional security and economic integration plans. What constitutes sufficient stability in this context remains unclear; the SOFA provides little by way of a wider angle focus beyond a militarized engagement, although a commitment to support the return of law and order suggests a possible policing role. Beyond that, there are currently no clear moves towards developing a broader strategy that would extend beyond the current ‘hard security’ counter-terrorism focus. A recent report from South African and Mozambican academics provides a framework of considerations that could be incorporated for a more comprehensive SADC strategy. This specifically calls for the development of an “effective and credible” countering and preventing violent extremism strategy from the foundation of current counter-terrorism commitments. This would necessitate a further investment in SADC’s mediation and conflict resolution infrastructure, which currently has very limited capacity. Such an approach, however, requires the government of Mozambique to take the lead; it is unclear if that is likely to take place.

Underpinning continued SADC involvement in the conflict is the issue of finances. SAMIM currently relies on self-financing, limiting the extent of the SAMIM deployment. Troop contributing countries will be able to provide some further support, but this is not a sustainable option. SADC has started the process of exploring funding options (through the European Union, the African Union, and the United Nations), but there are no clear pathways and certainly no guarantees in place at this juncture.